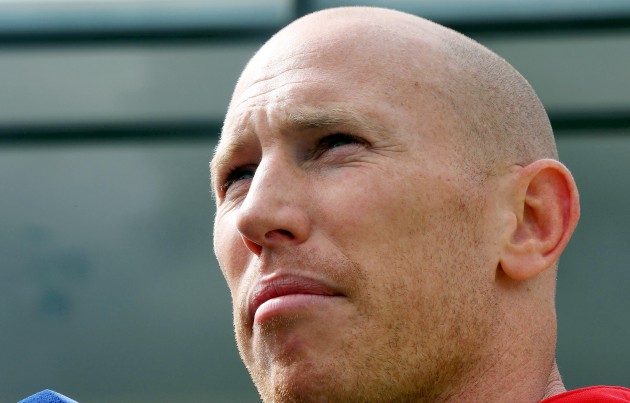

After 21 seasons of pro rugby, scrum-half Peter Stringer has finally accepted that his playing days are over. Rugby World pays tribute to the 40-year-old Munsterman

Irish legend Peter Stringer retires at 40

Peter Stringer finally called time this week, bringing the curtain down on a remarkable career that yielded 98 Ireland caps and more than 350 pro club or provincial appearances combined for Munster, Saracens, Newcastle, Bath, Sale and Worcester.

Along the way he won a Six Nations Grand Slam in 2009, three Triple Crowns and the 2006 Heineken Cup, but he will be remembered most for the outstanding professionalism that enabled him to play arguably the world’s toughest contact sport until the age of 40. Only Brad Thorn (Leicester, 2015) and Paul Turner (Saracens, 1999) have appeared in a Premiership match at an older age.

“From the age of five all I ever dreamed of doing was playing rugby. I cannot describe how it feels to have lived that dream for nearly all my life,” said Stringer. “The journey has been an uncompromising obsession filled with memories I will cherish forever.

“To the coaches who never saw my size as disadvantageous, thank you. To my team-mates who motivated and inspired me, thank you. To my parents and brothers, I could not have reached my goals without you. Here’s to the next chapter.”

Rugby World interviewed Stringer a couple of years ago when he had just won a player award at Sale Sharks. Here’s how we paid tribute to the Munsterman on that occasion…

Final days: Stringer in action last season for Worcester, the last of his five English clubs (Getty Images)

There were warm tributes for Chris Cusiter this week after the Sale scrum-half called time on a career that included 70 Scotland caps and one for the Lions, off the bench in that curious 2005 draw with Argentina on home soil.

At nearly 34, Cusiter has given professional rugby a very good lash. But in truth he’s had to play second fiddle in his final season to a man who will celebrate his 40th birthday next year.

Peter Stringer lost out to Cusiter in Lions squad selection all those years ago but he has never stopped driving himself on, determined to be the best he can be for as long as can be.

Jonny Wilkinson’s obsession with self-improvement is legendary but even he had the odd drink during his career; Stringer has never sipped alcohol or dragged on a cigarette, he exercises twice daily even when on holiday, and he thinks nothing of taking his own (mega-healthy) lunchbox to the airport when faced with an away match. Salmon and rocket anyone?

His single-mindedness means that his fitness levels are never in question – scrum-half is an especially unforgiving position in that respect. And more than three years after being let go by Munster, he has just been voted the Supporters’ Player of the Year at Sale.

“Peter Stringer has brought our back-line to life this season,” said director of rugby Steve Diamond when extending the player’s contract until next summer.

Northern rock: Spinning a pass away for Sale against Saracens in February 2016 (Action Images)

If his longevity is extraordinary, Stringer’s size is no less remarkable. At 5ft 7in and 11st 5lb (72kg) pretty much all of his career, he has, paradoxically, stood out from the crowd for most of a rugby journey that began with his home-city club Cork Constitution when he was six.

His small stature has led to him being treated differently in countless ways, subtle or otherwise. At UCC, his university rugby coach asked his parents for permission to pick him. After he was punched by Alessandro Troncon in a Six Nations match, the hotel cleaning ladies in Rome hugged him. And if someone needed to be bumped into economy class for a flight, no prizes for guessing who fingers pointed to…

Stringer recently published a fascinating autobiography. The tale of how he was mistaken for a mascot by parents, when leading out the Pres U13 team that he captained, opens one of the most brilliant and heart-rending chapters you could ever read.

Concerned by hearing expressions of disapproval that their son was allowed to mix it with far bigger boys in a physical sport, Mr and Mrs Stringer decided to enlist Peter on a growth hormone programme. Peter’s distraught reaction convinced them to abandon the idea and he has gone on to genuine greatness – 230-plus Munster appearances and 98 Ireland caps do not happen by accident.

Young star: In action for Pres during the 1993 Munster Schools Junior Cup final (Des Barry/Cork Examiner)

His size makes him well placed to discuss the merits of a recent call, by a group of doctors and academics, to ban tackling in schools on the basis that some children will get hurt.

“I wouldn’t change a thing from the rugby I’ve played. It would do a lot more damage if people only started tackling at 18. It would kill the game, ruin the professional game,” Stringer says unequivocally.

“Being coached properly is the main thing; you need the right technique. You start by tackling on your knees and everyone is at the same level, with relatively similar sizes and heights. If you learn from a young age, it’s easier to pick it up and it’s engrained in you. You have a base level doing it regularly under correct supervision.”

Rival Shark: Mike Phillips, signed from Racing, was another old hand at No 9 for Sale (Action Images)

Stringer says that even today, when making a tackle for Sale, he sometimes hears the voice of one of his former mini coaches yelling, “Take him by the legggggs!”

The Munsterman dismisses the suggestion that the legal height of a tackle should be lowered. In three and a half decades of rugby, he has suffered three concussions, none of them at school. “From my point of view, for a tall guy to tackle me below the sternum is very difficult. You see higher shots on smaller guys but I’ve no problem with that.”

The bigger they are… Tackling Bath’s Matt Banahan, a former team-mate, at the AJ Bell Stadium (Getty)

He has more sympathy for the idea of weight bandings for age-grade rugby, as occurs in New Zealand. There, youngsters of certain ethnic backgrounds tend to develop earlier and large playing numbers ensure that no one misses out.

“In some ways weight-related rugby would have been an advantage for me,” he muses. “If I’d played against guys of the same size when younger I’d have had more confidence going into contact and the ability to develop offloading skills. Whereas I found when taking contact that I was fighting my way to the ground, rather than having the power to go through a tackle.

“But if you’re a small player up against bigger ones from day one, you develop footwork to avoid bigger guys, and speed to get round them. Being small gave me a tenacity to survive that has stood me in good stead right through my career. If I’d been thrust into weight-related rugby, then a number of years later would I have been able to adapt to adult rugby?

Sandwich filling: Stringer has Mal O’Kelly and Alan Quinlan beside him for the anthem at RWC 2003 (Inpho)

“It’s an interesting one, there are pluses on both sides. Everyone is born with a certain amount of talent, with footwork and speed for example. If Jason Robinson, say, had played with same-size guys, would he have tried to run over them instead of step?

“By the time you get to senior level you’ll have missed out on years of sidestepping and evasive skills, and so might not be able to implement them in a game against bigger guys. You’ve got to face big guys at some stage. The earlier you do so, the better it is for your skill level.”

Stringer points out too the perils of asking, say, a big 15-year-old to play with 17-year-olds of a similar size but at a completely different level of emotional and social maturity.

“You’d be on dangerous ground there. At school especially, rugby is about the enjoyment factor. If you try to move people out of their natural age groups that could be taken away and you’d end up with a lot fewer people playing the game.”

So speaks a voice of experience and reason, a player who hasn’t allowed either size or age to hinder his ambition. This weekend Sale need a victory at Newcastle to try to secure Champions Cup qualification – and, as he completes his 19th season as a pro player, Peter Stringer will be at the heart of the challenge as always.

To buy Peter Stringer’s book Pulling the Strings, published by Penguin Ireland, click here.

Special delivery: His work ethic made him one of the best passers of a ball in the pro era (Inpho)