A 20-13 win for Wales in Paris was an exercise in graft with all of Warren Gatland's forwards stepping up. We analyse the integral roles played by Alun Wyn Jones and Luke Charteris

Now more than ever, rugby spectators are overrun by technicalities and statistics. The accessibility afforded to broadcasters means heightened scrutiny and overbearing focus on the game’s intricacies. These days you get laughed out of a pub if you cannot keep up with chat about choke-tackles and exit strategies.

That said, the old-fashioned art of being a nuisance to play against remains massively underrated. For all of Joe Schmidt’s meticulousness, Ireland are an inferior side without Peter O’Mahony – the niggly Munsterman whose wandering limbs transform every opposition breakdown into an awkward mess.

On Saturday evening in Paris, Wales conjured a win that was far closer to ugly than gritty. Nigh on 80 per cent possession in the first half yielded only a 6-3 lead as France somehow soaked up Warren Gatland’s hard-running strike-runners.

Though Les Bleus came back into proceedings after the break, the visitors prevailed. At the heart of a pivotal forward effort, locks Alun Wyn Jones and Luke Charteris were phenomenal. A contrasting couple – one an 87-cap icon, the other still uncertain of starting berth after a 53 Tests in a stop-start career – they combined brilliantly.

Here is a run-down of their contributions to a victory that kept alive Wales’ Six Nations title chances.

Gainline grunt

From the game’s very first phase, Charteris and Jones grabbed this clash by the cojones:

Both men lead Wales’ line-speed for their first defensive set, ensuring France’s maiden carry by Eddy Ben Arous is met well behind the ruck:

Arriving first at contact area, Charteris makes a muscular challenge, almost affecting a choke tackle by holding Arous above the ground:

Though the loosehead does wrestle his way to deck to avoid a maul forming, any attacking momentum has been completely sapped. Compare that inertia with this early carry from Charteris:

As this screenshot shows, the situation is not too dissimilar from that of Arous’ run above. The defensive line is set and can rush up in an organised manner:

The difference is dynamism. Charteris steams onto the pass from Rhys Webb and lopes up to the France 10-metre line, parallel to the back foot on the hosts’ side of the ruck and therefore beyond the gain-line. As he is felled, Jones is on the scene to hit the breakdown and recycle:

Finally, using his long arms to great effect (more on this later), Charteris shows impeccable technique to extend into a long ball presentation. Thus, he makes it doubly difficult for any France fetchers to get onto the ball and easier for Webb to whip it away:

Transferring the point of contact

For all their raw materials – pace and power throughout the side – Wales are at their most dangerous when adding a bit of guile. Even in the tight exchanges, Jones managed this.

First, there was an exchange with Gethin Jenkins, a neat offload setting the prop away and eventually winning a penalty and three points as Romain Taofifenua infringes at the ensuing tackle area:

Next, this slip pass to Sam Warburton provides an excellent example of transferring the point of contact, something New Zealand‘s forwards – not least Brodie Retallick – do brilliantly:

It may look rather innocuous, but this short shift brings about serious stress for defences. Isolating the moment Jones moves the ball, we can see the effect it has more easily:

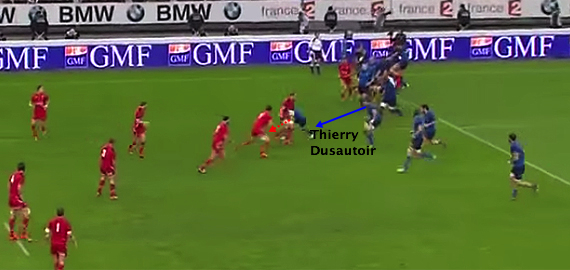

Essentially, as Thierry Dusautoir rushes up on his own, the pass gives Warburton space to attack a a classic defensive dogleg. Jones’ dexterity was also crucial at set-piece.

Off the top and into midfield

Jamie Roberts‘ hard running is the cornerstone of Wales’ patterns and the centre was in destructive form once again this weekend. The most effective platform to launch him off, as has been shown for years, is quick lineout ball from the tail.

This was a flawless demonstration of best practice, Jones’ taking Scott Baldwin‘s throw and feeding down in front of Webb so the scrum-half can take in his stride and pass immediately to Dan Biggar, who in turn finds Roberts:

Busting a gut

Sheer hard work, even in the exacting environment of Test rugby, is a valuable commodity. So much so, in fact, that one big effort can bring about a vital intervention.

Take this tackle from Jones, which forced France to spill on the hoof (even if the drop was deemed not to be a knock-on by referee Jaco Peyper):

The most impressive thing about this is how quickly Jones and Charteris adjust their position as Morgan Parra is brought down on the previous phase:

Stuck on the blindside following the lineout, the second-rows sprint around to the openside and join the defensive line as France continue their pacy phase-play. Jones scrags Arous and Roberts completes the tackle, forcing the ball loose as an offload is attempted.

Trundling on

The second half of this match was characterised by Wales’ rolling maul, which caused total havoc and brought a steady stream of points. Naturally, Jones and Charteris were extremely prominent, beginning here:

Charteris is employed as the front lifter as Jones takes and Wales are into their shape rapidly with the locks providing a watertight barrier between France and the ball. Notice how Jones is also communicating to the referee, bringing attention to Dusautoir’s offside position while his pack marches forward:

Though Jones is spun out by the defence and must rejoin the maul, Charteris remains a focal point at the front until Webb uses the ball – with a penalty won – on the edge of the 22:

There were two more instances like this later on, each synchronised efforts with Jones and Charteris alternating between lifting and jumping duties. Both drew offences out of a frustrated France pack.

Pure awkwardness

France’s Parra-inspired mini-revival after half-time was quelled when the scrum-half left the fray due to a knee injury. Even during it though, a spanner was thrown in the works every time the ball went near Jones:

Sofiane Guitone‘s cat-flap to Mathieu Bastareaud gives the Toulon cannonball an opening, but Liam Williams dives back to shackle him. Then comes Jones’ bit of intelligent irritation.

Without making an attempt to pick up or even challenge for the ball, he steps beyond the ruck to impede two French support runners:

He gets a shove from Guilhem Guirado for his trouble, but would not have cared at all. His aim, of slowing down the France attack just slightly, has worked.

Choking up

It is probably fair to say that Charteris has drawn just as much criticism as praise over his years on the international scene. Even during this performance, the 6ft 9in specimen endured a couple of clumsy moments.

That said, he has carved a niche over this Championship for dismantling lineout drives, using his arms like a crazed kraken to fight through the maul and engulf up the ball. He notched up another turnover here:

This is excellent work from Charteris. First, he resists the heavy-handed approach of Damien Chouly to move through the maul…

…before keeping his cool and, eager not to concede a penalty, checking with Peyper to see whether he is in a legal position:

Clearly told he is fine to carry on, the Racing Metro man then grabs Dusautoir. As the maul collapses, the ball remains above the ground:

Charteris has completed a turnover in a dangerous area of the field.

Try-scoring industry

Quite rightly, Wales’ only try of this game drew plaudits for Dan Lydiate‘s sumptuous flick pass:

But who are the first to the ruck prior to Webb’s half-break, just as Bernard Le Roux is loitering for a turnover? A fiercely determined duo, that’s who:

Losing to England means Wales must do it the hard way if they are to land yet more silverware in this tournament.

Beating Ireland will be excruciatingly tough. Still, you can be absolutely sure these two will give it everything.