We compare the offloading skills of New Zealand and France to discover why the All Blacks are masters of the art

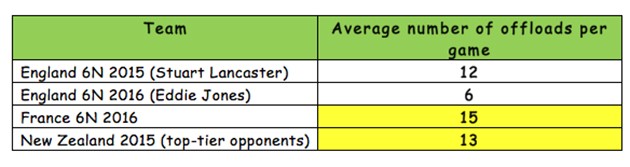

The recent Six Nations has thrown up an urgent question about the value of offloading in the modern attacking game. In this year’s Six Nations, France did it a lot but received very little reward for their effort, while England did it less than anyone else but profited in attack nonetheless.

What do the stats say? Let’s look at four important points of comparison:

New Zealand have been the world’s top offloading team, and Stuart Lancaster’s England vintage and Guy Noves’s nouvelle France have in some measure tried to copy them. While Lancaster’s England achieved a healthy degree of success, scoring 32 tries in the 2014 and 2015 Six Nations tournaments combined, France have generated a meagre seven tries in this year’s competition at an underwhelming average of 1.4 tries per game.

So why have New Zealand been so successful with the offload compared to France? The difference becomes apparent by comparing a couple of games where the offload tally has been relatively high. In their second Bledisloe Cup match last year, New Zealand offloaded 18 times on their way to a 41-13 victory over Australia, while France made 20 offloads in their 19-10 loss to Wales in the third round of the Six Nations.

The All Blacks like to shift the ball wide on their own terms, mainly on turnover or kick return ball. To this end they tend to position their No 8 Kieran Read – the world’s top offloading forward – in the channel between the 15-metre and five-metre lines on either side of the field. This gives a vital clue about where and when they intend to offload the ball.

Over 80% of New Zealand’s offloads occur in the wide channels, from the 15-metre line out towards touch. In the two sequences below, they are moving the ball wide after either a Richie McCaw breakdown turnover…

Or a lineout steal…

So the first rule – offload in the wide channels – is qualified by another condition: Offload in the wide channels after turnover. Why the rules? New Zealand want to get the ball to the area of the field where the defence is both thinnest in numbers and where the defenders cannot be as physical as they would like.

In both examples at 21:09 and 59:54, the All Blacks are moving the ball wide and forcing the Australian defensive line to chase them down either laterally or from behind. When the ball arrives at the first stopping point – the ruck at 21:18 or the drag-down tackle at 59:58 – there are only two Wallaby defenders in shot who can potentially influence the next attacking play.

As soon as this favourable situation is established, it is the mental trigger for “offload”. So at 21:21 Ma’a Nonu offloads just before contact to create a mismatch in space – Dan Carter against Wallaby lock James Horwill. Carter duly steps around Horwill at 21:23 before passing to Dane Coles for the All Black hooker to gallop over from 40 metres out for the score. In the second example, Ben Smith offloads to Colin Slade who drops it off to Conrad Smith, and Australia are forced to give up a penalty for the early tackle on the Kiwi centre.

Offloads in the midfield area between the two 15-metre lines are far less common, accounting for only 15-20% of total offloads. In this scenario the rule is: Offload from behind the defensive line, not in front of it…

In these two instances, with New Zealand No 9 Aaron Smith breaking around the ruck at 43:57 and Nehe Milner-Skudder making the cut in midfield at 47:09, the offload is only an option once the break has been made, it is not used to engineer that break.

A fourth rule can be called ‘maximum extension’ and is related to the offloading technique used by the All Blacks. At 43:59 (Aaron Smith), 47:14 (Milner-Skudder), 59:58 (Ben Smith) and 60:00 (Colin Slade), exactly the same technique is being employed. All the offloaders get maximum extension out in front to deliver a one-armed pass out of their natural hand. This movement takes the ball as far away from defenders as possible and gives the support player both a clearer view of the ball and more momentum on to it.

If we take a look at France’s offloads against Wales, we find a completely different picture to that painted by the All Blacks. Only five out of 20 offloads are made in the two wide 15-metre corridors; 75% occur in midfield.

In these examples, France are trying to offload where the defence is thickest and heavier physical contact is more likely. In the sequence from 44:52-44:59 there are never less than five Welsh defenders in shot and in the final two images at 44:58 and 44:59 the French attackers are outnumbered six to three.

Likewise after the two ground offloads at 75:24 and 75:26, the France attack finds itself at the same 2:1 numerical disadvantage. Lots of risk for very little potential reward!

In both sequences the French attack is also attempting to use the offload to break the first line of defence, rather than to capitalise on a line break that has already been made beyond it. Another All Black theory has been effectively turned on its head.

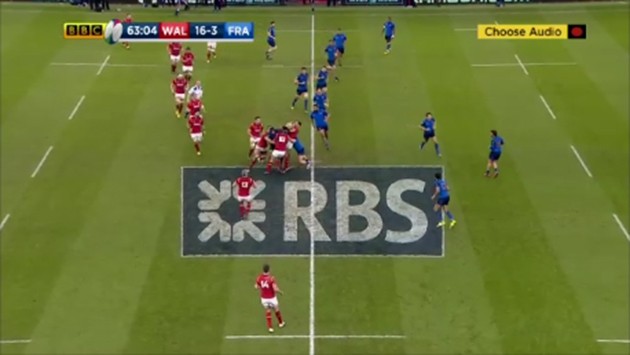

The technique on the offload is very different to that adopted by New Zealand. In all these examples, the French offloader is ‘standing tall’ and trying to push the ball away from him at chest level or above, he doesn’t get maximum extension. The ball is far closer to his body and he is attracting a lot of ‘flies’ or tacklers – two at 13:51 and 49:41, three in the Welsh choke tackle at 63:04.

Control of the pass is more difficult, there is more defensive interference and correspondingly little momentum on to the ball for the receiver. The pass at 13:51 goes forward, at 45:30 it is knocked on, at 63:04 the ball-carrier Jonathan Danty is held up and Wales win the turnover scrum.

The translation of ‘offload’ can be completely different in one culture (New Zealand) compared to another (France). How the offload is implemented, the situations where it has been identified as a positive and the techniques used to make it work, are all important.

With this in mind, it is perhaps no wonder Eddie Jones has cleverly chosen to minimise dependence on the offload with his new England side. The outlook and skills employed by the All Blacks take time to learn and refine, and to date no Six Nations team has either the technical ability or depth of understanding to imitate their achievements with it successfully.

For the latest Rugby World subscription offers, click here.