Book review: the angst and achievements of Ireland’s Rory Best

Lockdown or no lockdown, Rory Best’s autobiography is worth making time for. Only 11 men in history have played more Tests than the Ulsterman and his 14-year international career has provided a wealth of experiences and lessons that he is keen to share.

For the record, Best won 124 caps (102 starts) – the third most by an Irishman – and captained Ireland more times than anyone apart from Brian O’Driscoll. The hooker achieved a 63% success rate from his 38 matches as skipper.

He was part of nearly all the great Irish days of modern times: South Africa in Cape Town, the two wins against New Zealand, France in Paris, and the Grand Slam at Twickenham.

Grand Slam: Best says the 2018 win v England was the greatest Irish performance he played in (Getty)

If World Cup joy eluded him, as it has every Irishman since the competition sprung up, the more glaring omission in Best’s career comes with a red hue. He toured twice with the Lions, in 2013 and 2017, but got no further than the ‘dirt trackers’.

He was an unlikely candidate for stardom given his early years. Best grew up on a village farm in County Armagh and had an inbuilt reticence at odds with the globetrotting international rugby captain that he was to become.

In his teens, the “shy, fat lad from Poyntzpass” received a form asking about his availability for a summer training camp and he pretended he was going to be away so that he didn’t have to attend. At Newcastle University, he played social rugby with mates from his agriculture course. However, his talent couldn’t be ignored.

He played a bit for Newcastle Falcons at prop and finished his degree in Belfast so he could join Ulster. Remorseless set-piece work at Belfast Harlequins, under Andre Bester’s stewardship, helped Best become one of the best scrummaging hookers the game has seen.

Haven: Best with Tony Buckley and Cian Healy in 2010. He always felt at home in the scrum (Inpho)

Off the rails

Best can certainly be described as a late developer because his drinking and partying as a young man was far removed from the standards required of a professional athlete.

He relates how, after one big drinking session, he forced open a neighbour’s door because he thought it was his own house. His half-baked commitment was such that he asked Mark McCall, then Ulster’s head coach, if he’d be picked for a Celtic Cup quarter-final because he was meant to be best man at a wedding.

When Ulster won the Celtic League trophy in 2006 – Best’s only domestic trophy – he was party to some puerile trashing of a hotel room. It proved a watershed moment because at a subsequent disciplinary hearing, he vowed to give up drinking and he was true to his word.

Previously overweight and lacking mobility around the field, something reporter Neil Francis alluded to when writing that Best “waddled on for his first cap”, Best shed the excess weight and started to give pro rugby the respect it deserves.

Brotherhood: with older sibling Simon in 2006. Best’s weight hit 113kg in his younger days (Inpho)

He won Ulster Rugby Personality of the Year 2006-07 and, albeit a little uncomfortably, succeeded his brother Simon as club captain at the age of 24.

Internationally, he lost out more than he won in his selection duel with Jerry Flannery. But from his first Six Nations start, against Wales in 2007, Best played in 53 successive championship games over ten years – one shy of John Hayes’s Irish record.

And once Flannery retired in 2011, Best took centre stage. Exactly half of his huge caps haul came after the age of 30, when he played his most impressive rugby, and that fact alone should inspire those in the twilight of their career.

An Ulster legend: tackling Thomas Castaignede of Saracens during a 2005 Heineken Cup tie (Getty)

Technically speaking

The best chapter in the book concerns Best’s self-improvement as a player: his change of throwing technique in 2011, his scrummaging insights, the window he offers into a world of sweat and graft honing his skills.

He built a machine out of a cattle-feed bin to help his lineout throwing and, for the last eight or so years of his career, during the season he’d throw an extra 500 balls a week on his own.

He never really shook off a reputation as a flaky thrower, in part because of the nightmare of losing eight throws in defeat by the Brumbies on the 2013 Lions tour. Yet as Best points out, his stats overall weren’t to be sniffed at, including a 90% success rate across four World Cups.

When Joe Schmidt took the Ireland reins, he asked only that Best hit 30 rucks a game to help get quick ball. It was a task he was well equipped to do.

A theme of the book is Best’s insecurity, a desire to prove a point to either himself or to others who doubted him. Among those in his firing line is Graham Rowntree, the Lions scrum coach, who said the decision to pick Dylan Hartley, Richard Hibbard and Tom Youngs as hookers for the 2013 tour was not a difficult one.

“I thought he was out of order to be so disrespectful to a player who had been around for so long,” writes Best, who then replaced the suspended Hartley but lived with the feeling that the coaches didn’t rate him.

Red dread: Best leads out the Lions at Canberra. ‘The lineout was a disaster,’ he says of that defeat (Getty)

Tipping point

Media criticism wore him down, to the extent that more than once he came close to quitting in the months before Japan 2019.

“I’d turned 37 nine days before the Twickenham defeat (last August) and suddenly I felt old,” he says. “I was going to tell Joe I couldn’t play at this level any more. I was hampering the team. I didn’t want to go to the World Cup and let Ireland down. I didn’t want Ireland to fail because the guy who was supposed to be their captain and leader was weighing them down.”

Social media is no place for solace. After first being named Ireland captain in 2012, when O’Driscoll and Paul O’Connell were unavailable, one bigot tweeted: “No affence (sic) but how can a fat Protestant like you captain our country?”

Final bow: with his children Penny, Richie and Ben after the 2019 World Cup defeat by New Zealand in Tokyo (Inpho)

More garbage was directed his way after he posted a picture on Instagram in which his son Ben’s England football team bedclothes were visible in the background. Ben is a Spurs fan and has an English grandmother because Best’s mum Pat comes from Middlesbrough.

Best, in fact, could have played for England and we learn too that Pete Walton hatched a plan to keep the player at Newcastle in his younger days and then move him north so he could qualify for Scotland!

Neither happened, of course, as Best instead gave heart and soul to Ireland. His book is similarly committed, with perhaps only the chapter encompassing Paddy Jackson’s rape trial – at which Best acted as a character witness – being treated with undue brevity. “My focus was on supporting my friend. I had not thought I would upset anyone by attending court.”

Since his playing retirement, he’s been doing TV and commercial work. As for the future, he wouldn’t mind being the scrum coach for Ulster, the club he stuck with through thick and thin even when Leinster and some of the French clubs came knocking.

“I don’t necessarily want to pull a tracksuit on every day,” he told The Guardian. “Maybe a mentorship or consultancy role in rugby, or a scrum coach. Or maybe being more strategic in terms of almost being like a football manager.” He has a lot of knowledge to impart.

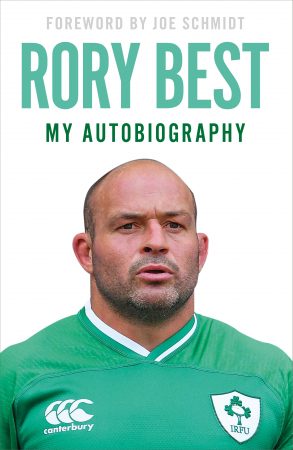

Rory Best: My Autobiography is published by Hodder & Stoughton, RRP £20. Written in collaboration with Gavin Mairs, chief rugby correspondent of the Daily Telegraph, it comes highly recommended.

Follow Rugby World on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

Spirit of rugby: Best’s last match was for the Barbarians against Fiji at Twickenham last November (Inpho)