The world's first global rugby super star Jonah Lomu has died leaving the game shocked and saddened

I last saw Jonah Lomu in London this September at a sponsors event for the Rugby World Cup. He was bedecked in a sharp blue suit, dapper brown brogues, yet what stood out was his easy smile, humility and approachability. He took time to speak to anyone around him – even us pesky journalists.

Sadly, it was clear that the years of kidney dialysis had taken their toll. Physically, he seemed to have shrunk, with stooped shoulders and an uneasy gait.

What was most interesting, however, was the reactions of other greats of the game. Will Carling – the man who famously called him a freak after the unforgettable 1995 World Cup semi-final – World Cup winners John Smit and Matt Dawson and Welsh dump truck Scott Quinnell all looked up to him. It was clear, they were no different to the rest of us mere mortals. Jonah was, and still is, the man. The first global superstar of rugby union.

Of Tongan descent, as a kid, he brought up in the tough Mangere district of Auckland, on the South Island where gangs and violence were commonplace. Thankfully, Jonah took a different path. Prodigiously gifted, he broke virtually all athletic records at Wesley College, and was destined for greatness from a young age.

At 19, he played in the Hong Kong Sevens, then a trial run for graduation into the All Blacks, and obliterated the opposition.

Months later, he lost his first two Tests in an All Blacks shirt against Les Bleus, with John Kirwan on the other flank before having to wait nearly a year to pull on the silver fern. New Zealand’s secret weapon.

What happened over the next six weeks in South Africa, not only changed Jonah’s life, irrevocably. It changed rugby. Legend has it that Rupert Murdoch, after watching Lomu swatting and steamrollering English defenders, made it his business to catapult rugby into the professional era, by offering an eye-watering sum to screen SANZAR games.

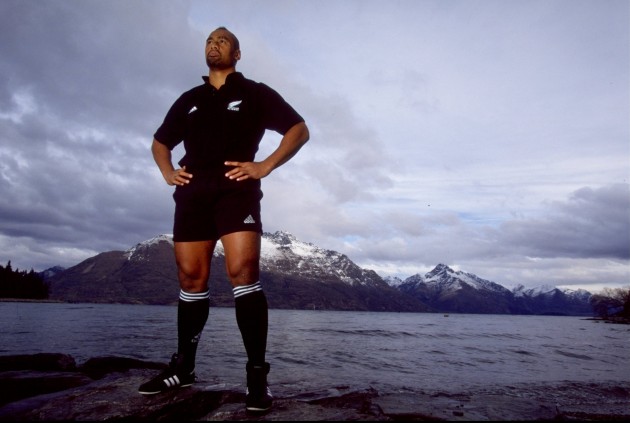

While Kirwan had been a big man, at 6ft 4in and over 16st, Lomu was in the WWE ranks. He stood at 6ft 5in and weighed a shade under 19st. The problem for defenders is that he could also run like the wind. He was clocked at 10.7secs over 100 meaning he was virtually impossible to bring down single-handedly. As Bill McClaren famously said: “And there goes Jonah Lomu, proving once and for all that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line.”

He scored seven tries in the tournament and was denied a World Cup winners medal only after a heroic defensive effort by the Springboks led by his old foe Joost van der Westhuizen.

Despite a king’s ransom being dangled in front of him by NFL’s money men, Lomu stayed true to the All Blacks, going on to score 37 tries in just 63 appearances.

Lomu said recently that his health problems – he was diagnosed with a rare kidney disorder, nephrotic syndrome in his early twenties – meant he played rugby with the handbrake on. It makes you shudder to think what he could have achieved if fully fit.

The world again regaled at Lomu’s freakish strength at the 1999 World Cup, where he scored eight tries, including a jaw-dropping individual effort against England, before the French dumped the All Blacks out of the Cup. One defining memory from that game stands out, however. Xavier Garbajosa, the French full-back, throwing himself out of the way, as if avoiding an oncoming freight train, as Lomu barrelled over. The tournament was a poorer place without him.

By 2002, he had played his final Test for the All Blacks, at just 27, with his health slowly preventing him from playing at his peak of his powers.

In retirement, Lomu has spent time travelling, mentoring kids and acting as an unofficial ambassador for rugby. Loved and revered around the world, he was in the UK for a speaking tour only last month.

Jonah’s untimely death, less than a year after another of New Zealand’s favourite son’s, Jerry Collins passed away will leave rugby with a heavy heart and thoughts must finally go out to his wife Nadene and boys Brayley, six, and Dhyreille, five. Jonah said in a recent interview that his goal was to see his boys into adulthood. Tragically, this will no longer happen, but we’re sure will be left in no doubt about the legacy their father has left in the coming years.

Rugby is in mourning. Rest easy, big man.