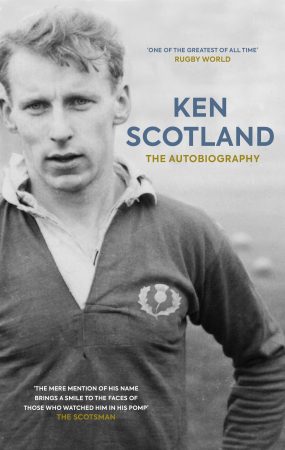

More than 60 years after starring for the Lions, the former Scotland full-back remains as sharp as a tack. Rugby World laps up the wisdom found in his recent autobiography

Ken Scotland, the Lion with a romantic touch

You’re never too old to write your memoirs, as Ken Scotland has shown. Born a couple of weeks after Jesse Owens was winning all those gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, the now 84-year-old Scotland has penned his autobiography – without recourse to a ghostwriter – some six decades after the high point of his distinguished rugby career.

The Scotsman was 22 when he departed for the 33-match, five-month 1959 Lions tour of New Zealand, Australia and Canada. He was to play five of the six Tests, four at full-back and one at centre, and was named as one of the five Players of the Year in the NZ Rugby Almanack.

Scotland kept a diary of the tour and records its highs and lows with assiduous attention. The Lions averaged five tries a game and, despite little meaningful second-phase ball to play with, their Test back-line forged a reputation as one of the best of all time.

Scotland, 5ft 10in and 11st 2lb, was pivotal to the Lions’ exploits, not least because of a versatility that saw him occupy every position behind the scrum except wing. Former Lions captain Arthur Smith rated him the best passer of a ball he ever played with, while Tom Kiernan, the 1968 Lions skipper, called Scotland the finest player of his generation.

Small wonder: Scotland (front row, second left) in the Heriot’s School first XV team photo of 1952-53

He was a creator, not a finisher, and racked up 27 Scotland and five Lions caps before retiring from international rugby at the age of 28. “He played classical rugby with a romantic touch,” says veteran journalist Allan Massie in the foreword.

Scotland’s book charmingly evokes the days of old when young men had to do two years of National Service, and a pie and pint in the NAFFI cost seven and a half pence. There’s no tittle-tattle; in fact, the only discordant note that springs readily to mind is a “decidedly frigid” relationship with next-door neighbours in Berwickshire.

Scotland was educated at George Heriot’s School and as a player modelled himself on Irish great Jack Kyle, who he watched in the flesh just two or three times (there was no TV).

His other sporting hero was Godfrey Evans, the Kent and England wicketkeeper, and Scotland was later to play for his country at cricket. He once hit scores of 136 and 138 in the space of two days in senior club cricket.

Army detail: on parade with the Duke of Edinburgh and some serious top brass

He was still a schoolboy when he helped Scotland beat England 29-3 in an age-grade International at Richmond, having a hand in all five Scottish tries.

It was the only time he played on a winning side against England, the biggest regret of his career. Perhaps most painful was a 3-3 draw in 1962, when he missed a couple of kickable penalties near the end that denied the Scots a Triple Crown.

His Test debut came in Paris in 1957, when he played at full-back despite almost no experience in the position. His usual role was fly-half but that spot was filled by Micky Grant, the regular full-back for Harlequins. Such were selectorial whims at that time!

Scotland hadn’t kicked for any of the representative teams he’d played in since leaving school, yet was appointed goalkicker on his debut. He had a pretty average game but slotted the points in a 6-0 win – he was up and running.

Being capped by Scotland ticked off one of the three ambitions he had when leaving school. The others, both also happily achieved, were to pass a Latin exam so he could get into Cambridge and to marry his sweetheart Doreen.

Life aim: marrying Doreen on Easter Monday 1961, almost seven years to the day after their first date

He and Doreen have moved around a lot, Scotland’s career in management consultancy – often centred on improving factory productivity – taking him to various locations in England’s East and West Midlands, and to County Down, before he returned north.

On being posted to Aberdeen, he played for the Aberdeenshire club and for North Midlands for seven seasons, a period that coincided with him losing his Test place to Stewart Wilson.

He retired from first-class rugby aged 33 in 1969 but, with sons playing at Heriot’s, he started refereeing and joined the Heriot’s FP committee. He was chairman of selectors in 1976-77 and used to have selection lunches with club captain Andy Irvine.

Scotland was still playing a bit of social rugby in the mid-Seventies and in one game against Merchiston Castle School came up against a young scrum-half called Roger Baird, later an international winger. The opposition in Scotland’s very first game in senior rugby, at the 1955 Kelso Sevens, had included Baird’s father, also called Roger.

Robbed! Scoring v NZ Maoris on the 1959 Lions tour – it was wrongly disallowed for a ‘knock-on’ (Getty)

Scotland’s work career, including several years looking after a castle on the Isle of Arran for the National Trust, makes interesting reading. Not least when Neil Armstrong arrived by helicopter for a look-around – the astronaut had Scottish roots in Langholm. Today Ken and Doreen live in retirement in Edinburgh, where Ken watches club rugby most Saturdays.

He says that backs in the Sixties had no incentive to pass the ball because of the laws. In the aftermath of the infamous Scotland-Wales game of 1963, the one cited as having 111 lineouts, he was asked to write an essay for a journal. He reproduces it in his book and it details how rugby lost its way from 1950 to 1965, as the equilibrium between backs and forwards tilted too far towards forwards. The result was years of defensive, negative rugby.

Specialisation among forwards took away the uncertainty of who would win the set-piece contests – with a knock-on effect on how sides set up. “It became virtually impossible to start a handling movement directly from a scrummage or lineout,” he writes.

His remedies for the space-starved modern game are equally engrossing, so much so that RW contacted him for an article that is published in our forthcoming February 2021 issue. Scotland was pottering about in the garage, busy as always, when we called him.

Ken Scotland: The Autobiography is published by Polaris, RRP £17.99. Give it a read.

Can’t get to the shops? You can download the digital edition of Rugby World straight to your tablet or subscribe to the print edition to get the magazine delivered to your door.

Follow Rugby World on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.