We take a look at holes in England's defence against Ireland and how Wales might look to exploit these issues in the Six Nations

For the first time in the 2016 Six Nations, England’s defence was put under sustained pressure during the second half against Ireland. Some gaps began to appear, starting with the D from set-piece.

Tight midfield from set-piece

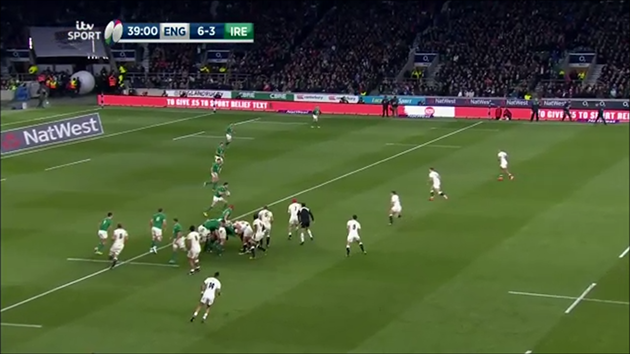

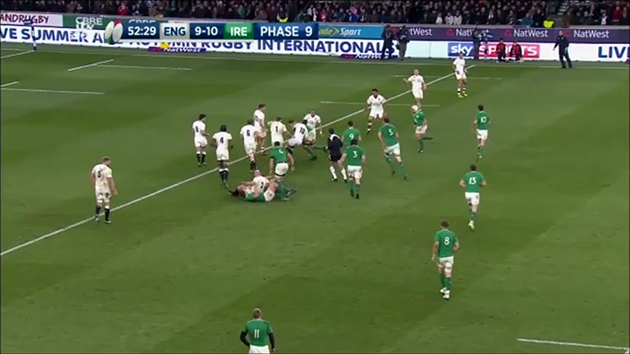

From both lineout and scrum, England’s midfield of 10 George Ford, 12 Owen Farrell and 13 Jonathan Joseph defend very tight. This is particularly obvious in the picture from a scrum right at the end of the first half.

England start with decent spacings, with about seven metres between Ford and Farrell and ten metres between Farrell and Joseph.

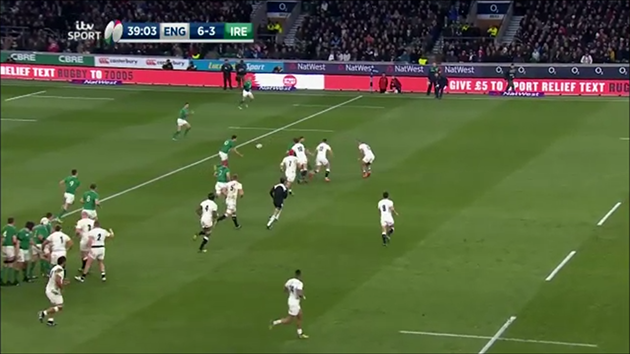

However, after the Ireland fly-half Johnny Sexton makes the second pass to his inside-centre Stuart McCloskey and begins to wrap around him, the midfield D suddenly becomes very condensed around the physical threat of McCloskey (for which read Jamie Roberts for Wales). The England 10, 12 and 13 are all in a ‘box’ of no more than four square metres at 39:03.

This leaves the widest defender Joseph running at a 90-degree angle towards touch to make up ground on Sexton as he gets the ball back from McCloskey. If Sexton passes immediately to Rob Kearney outside him, there will be plenty of space to run into on the far side.

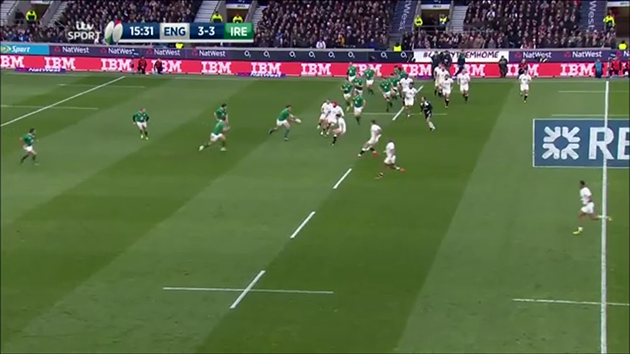

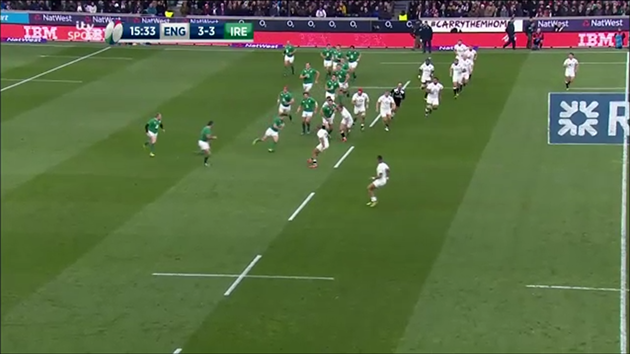

A similar scenario occurs from the lineout at 15:30. With the England 9 Ben Youngs starting in the tram-lines, neither 2 Dylan Hartley nor 7 James Haskell have the speed required to put much pressure on Ireland’s first receiver (McCloskey).

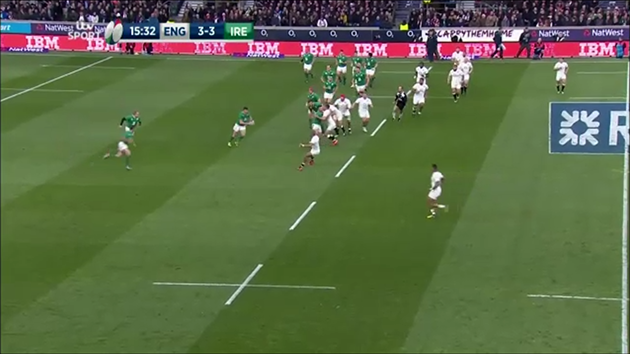

This in turn means that Ford is pinned to McCloskey’s outside shoulder, with Farrell only two metres away and already angled slightly out-to-in and ready to help out. If the blocker out in front (13 Robbie Henshaw) continues his run through Farrell’s inside shoulder he will attract the tackle legally and free Sexton to run through the gap between Farrell and Joseph. Instead he stops and puts hands on Farrell, and that draws the interference penalty from the referee and nullifies the break.

England’s defensive ‘personality’: line speed not line integrity

England want to get off the line and move upfield at speed in order to place maximum pressure on the ball-handling of the opposition. They are not too worried about maintaining a flat line of defence. This suits their ‘outlaw’ image under Jones, but can create holes when either line speed or communication is not consistent across the board. So at 39:12 the line looks pretty ragged:

Both Ford and Farrell have drifted off the line and are thinking of crossing over to the far side of the D, where the last defender (6 Chris Robshaw) is already ahead of the man inside him, Joe Marler.

Both Ford and Farrell have drifted off the line and are thinking of crossing over to the far side of the D, where the last defender (6 Chris Robshaw) is already ahead of the man inside him, Joe Marler.

In the event, Farrell gets no further than play-side guard before he turns to rush upfield on to Henshaw.

The two defenders underneath Farrell (George Kruis and Dan Cole) actually end up defending directly behind Farrell, rather than alongside him as Henshaw makes the break!

Pressure on the aerobic capacity of England’s forwards

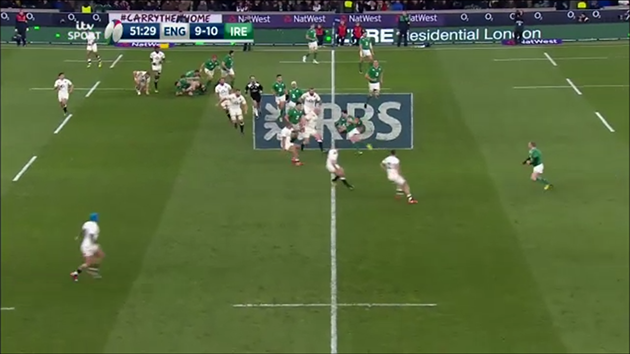

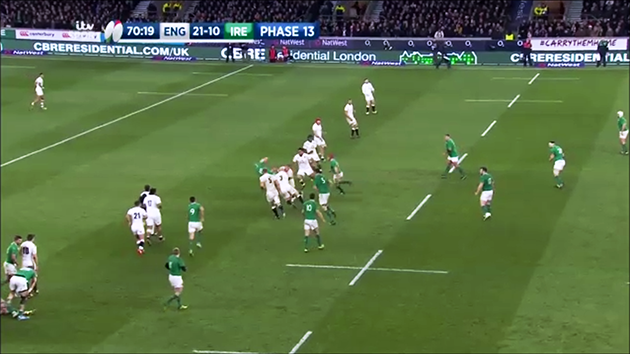

The demand to rush hard upfield on every play places an enormous aerobic strain on England’s forwards. They have to do an awful lot of running up and down the field in defence. Look at this snapshot at 51:29 in the second half:

Both Farrell and Ford are rushing well past the ball on the outside and poor old Cole underneath them has no time to set his feet for the tackle as Sexton cuts inside – he can only throw out an arm in despair as the Ireland outside-half streams past him. I believe it was the constant demand to rush upfield which led to the aerobic wind-down in England’s starting tight forwards and Ultan Dillane’s clean break at 70:19 – another failed arm tackle by Hartley and Cole.

Vulnerability to blocking plays

England are also potentially vulnerable to blocking plays – defenders cannot ‘check off’ attackers one by one as they would when continuing to move sideways in the drift because they are running a full course straight upfield. Apart from the Henshaw example at 15:32, at 64:51 after driving upfield for a few metres Mako Vunipola has no ‘out’ left in him to shift on to Sexton and gets blocked out by Nathan White.

Sexton’s break set up the ‘try-that-wasn’t’ for Henshaw in the corner.

Attacking George Ford’s channel

Ford is a smart defender but England are using him in the line, and Ireland always had a decent bread-and butter option by aiming a heavier ball-carrier down his channel. In the following, Donnacha Ryan simply drops his shoulder and carries Ford fully five metres downfield to set up a positive ruck.

Wales have considerably more size and power in their back division than Ireland, so in theory it will be easier for them to exploit these potential weaknesses in the England defence. But will the plan survive first contact with the enemy?

For the latest Rugby World subscription offers, click here.