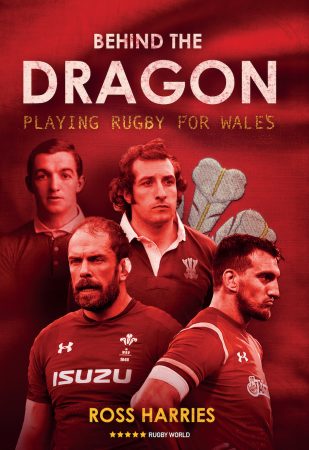

A new book charts the triumphs and tribulations of Welsh rugby through the players' own words. Rugby World finds Ross Harries's Behind the Dragon hard to put down

Behind the Dragon – an enthralling history of Welsh rugby

Polaris Publishing was only established in 2011 but already it has built up a substantial rugby catalogue. At its heart is the ‘Behind the’ series in which a country’s rugby history is told predominantly through the words of the players who wore the national shirt.

Surprisingly perhaps, given their fervour for the sport, Wales are the last of the four home nations to feature in the series. It’s been worth the wait, however, as Behind the Dragon emulates the excellence of the works on England, Scotland, Ireland, New Zealand and the Lions. The South Africa version, Our Blood is Green, is due out in September.

Guiding the Welsh ship is Ross Harries, best known as a TV presenter for Scrum V and the Guinness Pro14 but also a highly accomplished writer. He sets the context beautifully for each chapter, initially focusing on the early decades when Wales recovered from the shock of a debut-Test shellacking by England in 1881 – 0-82 by today’s scoring system – to launch the first of their Golden Eras at the start of the 20th century.

Author: Ross Harries, here in his presenter role for Premier Sports, has pulled the book together (Inpho)

Gwyn Nicholls, part of the innovative Cardiff team of that period, says that trying to stop his fellow centre Arthur Gould was “as difficult as trying to catch a butterfly in flight with a hat-pin”. Gould was Welsh rugby’s first celebrity and we learn of the greats that followed, men like Viv Jenkins, Wilf Wooller, Haydn Tanner and Cliff Jones.

Rowe Harding, another famous Welshman who toured with the 1924 Lions, is one of the first to take a pop at the snobby approach to professionalism that pervades much of rugby history. “The whole attitude towards amateurism is hopelessly illogical. Every amateur who is not a fool or a genius has his price,” says the late winger.

2019 glory: Alun Wyn Jones and team-mates celebrate Wales’ fourth Grand Slam this century (Getty)

Examples of pernicious pettiness litter the book but here are just a couple.

Ossie Male was ejected from a train carrying the Wales team towards Paris in 1924. His crime? He had unwittingly broken a WRU by-law stating that no player could take part in a match within six days of an International. Male had played for Cardiff five days before the Test because he needed match fitness having been sidelined by injury.

Flake news: Just gimme what she’s having! (Inpho)

Fast-forward to the Seventies and little had changed. The Wales players would go to the cinema on the eve of a match. “Gerry Lewis was the old mother hen and he’d get the ice-cream order in,” explains Phil Bennett. “Twenty-four ice creams. And Geoff Wheel would pipe up, ‘Any chance of a flake?’ ‘No, no, Bill Clement (WRU secretary) said no flakes.’ They were too mean to give us a bloody flake.”

If the WRU takes a pounding, so do the national selectors. The chopping and changing was such that in the 21 Tests between the end of World War One and March 1924, Wales used 99 players. The joke was that you would be picked one month and attend a past players’ reunion the next.

Fly-half Bennett, one of the most vocal critics featured in the book, says that after a four-minute cameo on his debut when he didn’t touch the ball, he was picked on the wing against the 1970 Springboks – a position he hadn’t played since he was 11.

“I pointed that out to the selectors, who brushed it aside, saying I was a good enough footballer to cope. Those were the days when wingers threw the ball into the lineout and I didn’t have the faintest idea what I was doing. After a disastrous practice session with Delme Thomas where I tried underarm, overarm and everything in between, the big man looked at me in exasperation and said, ‘Phil bach, just lob the thing in and may the best man win!’”

Centre stage: skipper Phil Bennett, holding the ball, with the Wales team that faced France in 1977 (Getty)

Later, another notable Welsh No 10, Gareth Davies, was warned that the Wales XV to face England would be announced with ‘AN Other’ at fly-half as the selectors wanted to keep their options open, effectively using an upcoming Cardiff-Swansea game as a trial.

Davies, as the incumbent and a man who had served his country with distinction, was so put out that he told the WRU he would quit if the team was released with the question mark at ten. The union went ahead and did it anyway and Davies, having outplayed his rival Malcolm Dacey in the Cardiff-Swansea match, duly kept his word – even after the WRU came back to him cap in hand asking him to reconsider.

The content on the sensational Seventies will absorb rugby fans of any nationality. From Gareth Edwards’s incredible solo try against the Scots, when he finished caked in red shale, to Bennett’s breathtaking team effort at Murrayfield, Wales played mesmerizing rugby that even the modern-day Grand Slam sides forged by Warren Gatland can’t get close to.

Above the rest: No 8 Mervyn Davies, one of the rugby greats, wins lineout ball for Wales (INA/Getty)

The forwards’ part in those glory years is sometimes overlooked, although not by the backs of that time. JJ Williams says of the legendary Pontypool front row: “The three of them had a sinister aura. They were ruthless killers on the field. When you looked across the dressing room at those three, you knew that if trouble broke out on the pitch, they’d be the ones dishing out the punishment.”

Barry John, who expresses his regret at retiring so young because of the “relentless, cloying attention”, owns just one piece of memorabilia: a Grogg of the 1971 Grand Slam front row of Denzel Williams, Jeff Young and Barry Llewelyn.

The class and consistency of those sides gave way to the chaos of the Eighties, when Wales fell a long way off their pedestal. They had been robbed of victory against the All Blacks in 1978, but a decade later in three meetings across 1987-88 lost the try count by 26-2.

The traditional style of rugby, with forwards running the width of the pitch following the ball, had become outdated and, despite a third-place finish at the inaugural World Cup, Wales remained in disarray for years as players jumped ship to rugby league and coaches came and went in a managerial merry-go-round.

The nadir was probably a 70-point hiding by NSW and a brawl among Wales players at the post-match dinner that followed a thrashing by Australia.

The chapter on Wales’ 1986 summer tour, when they beat Fiji, Tonga and Samoa, is one you will probably read open-mouthed. The match violence and primitive conditions in Tonga at the time were so far off the scale that if it happened today the South Pacific nation would surely incur a lengthy ban. Different times indeed.

Rose cutter: Adrian Hadley, left, helps stop Jon Webb during the 1987 World Cup quarter-final (AFP/Getty)

And so eventually to professionalism, with the arrival of the Great Redeemer, Graham Henry, and the false dawns that preceded a long-awaited Grand Slam in 2005. Harries flew to Dublin to chat to Mike Ruddock, the coach of that 2005 team who resigned less than a year later amid more political turmoil and accusations that his role in the Slam was overstated.

You can imagine the winks with which Ruddock told Harries: “People say I’m a lucky coach. I am a lucky coach. It’s extraordinary how lucky I’ve been.

“I won two championships with Blaina, and got the post-war try-scoring record in Cross Keys. Swansea were second from bottom when I took over, and I was very lucky to win the league with them the next year.

“Two years later, we won it again, and won the Welsh Cup in between. We beat Australia when they were world champions. I was lucky enough to win the Irish interprovincial title with Leinster. I’ve finished top of the league four times out of seven attempts in the All Ireland League where you suffer a massive turnover of players. I’ve been lucky many times.”

Lucky charm: Mike Ruddock, right, raises the Six Nations trophy in 2005. A year later he was gone (Getty)

Moving into the current decade, Sam Warburton is particularly fascinating on overcoming self-doubt and the chapter on the 2011 World Cup, when his controversial red card realistically cost Wales victory over France in the semi-final, is another belter.

Warburton reveals how he expected to be vilified, in a similar manner to the treatment meted out to David Beckham in the 1998 FIFA World Cup, but for one of the few times in his life he was wrong. The disciplinary hearing the next day was walking distance from the team hotel down a busy street lined with bars and outdoor cafés.

“I was dreading the reception I was going to get,” Warburton says. “Within minutes, someone clocked me and Gats, and I braced myself for a barrage of abuse. The bloke stood up and started clapping. Others soon followed suit and it set off a Mexican wave of applause. I’d been sent off in a World Cup semi-final, yet here I was getting a standing ovation on the streets of Auckland. I was overwhelmed with emotion. I’ll never forget that.”

Pivotal moment: the tackle by Sam Warburton on Vincent Clerc that saw him sent off at RWC 2011 (Getty)

A final extract is worthy of reproduction here. One player admits that Welsh people are brought up to hate the English. Instilled racial hatred does not belong in modern society, so it’s refreshing to hear Dan Biggar go against the grain when discussing the country in which he now plays his club rugby.

“Ninety-nine per cent of our fans will tell you that beating England means everything. I don’t see it like that,” says the Saints fly-half. “Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy beating them, but if you offered me one victory against the All Blacks in return for losing every match against England for the rest of my career, I’d take it. We need to be bigger than just beating England.”

Well said. And right now, as European champions and No 2 in the world, Biggar and Wales could have it all because they have the potential to beat both England and New Zealand and anyone else who might cross their path at the coming World Cup in Japan.

On the receiving end: Dan Biggar would love to experience victory over the All Blacks (Getty Images)