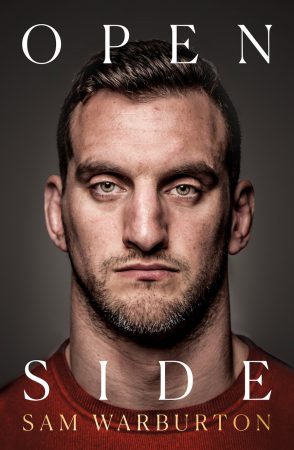

A powerful new book by Sam Warburton, the former Wales and Lions captain, lifts the lid on the physical and mental strains that led him to quit playing rugby at just 29

The heavy toll that stopped Sam Warburton

On the eve of Japan 2019 comes a reminder of a man who was meant to grace it. Sam Warburton retired from rugby 14 months ago at the age of 29 and will watch from the studio as Wales pursue a world crown to go with their three Warren Gatland-inspired Grand Slams.

Warburton’s book, Open Side, is published today and puts the final seal on a playing career that he admits himself is slightly short of legendary status.

“I don’t see myself in the very top drawer of those who’ve played the game,” he writes. “I was at the top of my career for only six or seven years, whereas men like Brian O’Driscoll and Paul O’Connell were at the top of theirs for much, much longer. I won 74 caps for Wales; Richie McCaw won exactly twice that number, 148, for New Zealand.”

Doing the robot? Warburton at an event for Land Rover, a Rugby World Cup 2019 sponsor (Getty Images)

If the book has a theme it is the mental and physical toll of playing elite-level rugby, with Warburton stuck in a recurring cycle of injury and rehab in-between his feats on the field. All told there were more than 20 significant setbacks, from the torn hamstring playing for Glamorgan Wanderers to the stinger in Cardiff Blues training that precipitated neck and knee surgery and ultimately led to him quitting the game.

The final straw came when the pain in his knees prevented him playing on the trampoline with his daughter Anna.

“My body just couldn’t take it anymore. You could leave me out for scrap and the tinkers would take me away,” he says. “I’ve got a pin in my left shoulder, another pin in my right shoulder, a plate in my jaw and another in my eye socket.”

He thus closed the door on a career that brought highs and lows in near equal measure.

Trucking it up: carrying hard against France at the Millennium Stadium during the 2016 Six Nations

The book, written in conjunction with Boris Starling, follows other works by Warburton on his 2012 Grand Slam year and 2013 Lions triumph in Australia. If you read those then some of the content will be familiar, and naturally there is also overlap with the recent BBC documentary Full Contact, in which Warburton says: “Being a player is full of stress and nerves and anxiety and pressure. I found it hard playing pro rugby.”

That much is clear from Open Side. Among several startling statements in the book, he says he wanted to flee the 2017 Lions tour, ringing his mum from his Wellington hotel room to tell her he’d had enough and could hop on a plane home before anyone would realise he’d gone!

Road to glory: Warburton and Gareth Bale in 2007. They attended Whitchurch HS (Huw Evans Agency)

He doesn’t mind telling us when he cries or sings to his dog over the phone or gets so sick with nerves whilst dating his now wife, Rachel, that he throws up.

Such human frailty is endearing and completely at odds with the physicality and courage he brought to Wales and the Lions on the pitch. In the second Lions Test of 2013 in Melbourne, with his leg trapped in a ruck as James Slipper made a clearout, he suffered an 8cm tear in his hamstring yet still got to his feet to stand in the defensive line until the next stoppage in play 55 seconds later. Clive Woodward called Warburton’s 65 minutes “the most outstanding performance I’ve ever seen from a Lion”.

The flanker had been equally monumental in the RWC 2011 pool match against South Africa, winning six turnovers and making 23 tackles in a losing cause, and there is no doubt that when the stakes were highest he produced his very best.

Painful exit: being helped off the field after the hamstring injury that ended his 2013 Lions tour (Getty)

There was a raging intensity about him that fuelled his explosive power, and when in one match he loses patience with the off-the-ball shenanigans of Wallaby Michael Hooper, he hisses at him: “Touch me again and I’ll cut your throat.”

It is Hooper’s partner-in-crime, David Pocock, that Warburton rates highest as an openside flanker. “He was consistently my most difficult opponent and the only one I think who got the better of me over the course of all the matches we played,” says Warburton, who picks him in his Best International XV.

Each chapter centres on a rugby ground of special significance to him and there are sections on the different aspects of leadership – and excellent stuff it is too.

One of my proudest moments in a rugby shirt: the British and Irish Lions tour to New Zealand. A seismic tour and my last game ever. My autobiography Open Side is out this week – pre-order your copy here: https://t.co/ak92ZjB9Uv #openside

— Sam Warburton (@samwarburton_) September 16, 2019

His refusal to sit in on selection meetings, because he wanted to be treated like anyone else, helped drive him to higher standards and he effectively ‘deselected’ himself ahead of the 2017 Lions first Test by speaking frankly to Gatland about his form at that stage.

He says of that tour to New Zealand: “For six weeks you’d have thought it possible to dedicate yourself totally to the cause, wouldn’t you? For six weeks you could leave no stone unturned when it came to making sure you performed at your absolute peak: eat right, sleep right, stay off the booze as it’s bad for recovery from inflammation, stay away from the blue light of mobile phones, and so on.

“But I reckon only 20% of the boys could honestly say they did that for the duration of those six weeks, which, given that we took 41 players, means around eight players. When you think how close we came (to winning the series instead of drawing it), would it have made a difference if everybody had done that? Very possibly.”

Jackal master: Warburton steals the ball but could the Lions have done more to win the NZ series? (Inpho)

Warburton proposes a series of actions in aid of player welfare before signing off, including enforcing Law 15.7 – concerning binding at the ruck – to protect jacklers.

With copious media work and a WRU ambassador role, he’s enjoying his retirement immensely and cites one-to-one mentoring and the Lions manager role as future objectives.

He will go down as one of the great players but an even better captain for his ability to exhort his team-mates to new heights – as with the Rorke’s Drift-style rhetoric in that lineout against England at RWC 2015 – or exert influence on referees.

“If he wasn’t the best player then he was going to die trying to be the best player,” says O’Driscoll in that BBC documentary. “In training, in matches, he just tried to get every ounce he possibly could out of his performance. And if that doesn’t lead and inspire, I don’t know what does.”

For all the latest news, follow Rugby World on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.