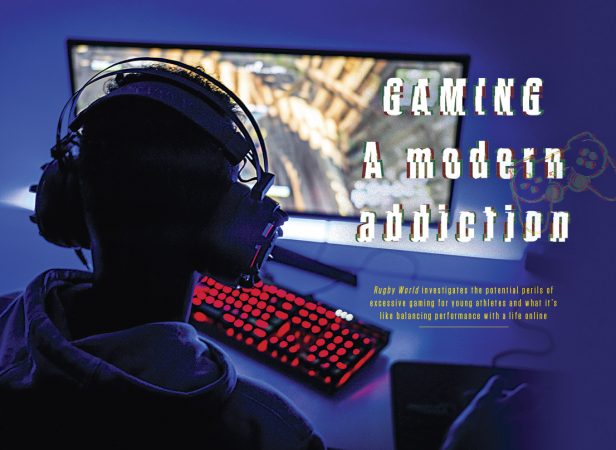

Rugby World investigates the potential perils of excessive gaming for young athletes and what it’s like balancing performance with a life online. This report first appeared in the mag in October

Gaming: a modern addiction

LIFE IN the real world was a painful echo as Cam Adair disappeared into addiction.

Growing up in Alberta, Canada, the young ice hockey hopeful learnt about the crushing cruelty of his peers and sought refuge online. As he explains of his teenage years: “I experienced a lot of bullying at school and on my hockey teams, and really gaming was a source where not only could I be someone else but I had more control over who I was and how people engaged with me.”

Adair talks openly of gaming addiction devouring ten years. He spent up to 16 hours a day gaming. He dropped out of school. He lied about having jobs. At his breaking point, he drafted a suicide note.

Wonder what that has to do with rugby? Today Adair speaks internationally about his experiences with this very modern affliction and now works with EPIC Risk Management, a consultancy set up to minimise gambling harm. They have put on seminars and workshops for top football academies on the dangers of gaming to excess and in particular the wreckage of spending outwith your means – looking at loot boxes (think of a virtual treasure chest you can purchase in-game) on games like FIFA or at online casino games, or esports betting. EPIC approached Rugby World about the potential to highlight the risks for young rugby stars.

Cam Adair (EPIC Risk Management)

Approaching one of rugby’s well-known youth coaches, we were told “It is a problem”, and one worth looking into. One other prominent figure from sports journalism revealed to us they too had experience of their own child spending around £800 of the parents’ money, without their knowledge, on FIFA loot boxes.

Which talks to fears many parents around the country may share. But it’s our intention to look at the potential dangers for promising athletes, as well as the positive sides of a lifestyle that appeals to more and more young adults. You can’t decry a whole culture but we can raise awareness of the pitfalls.

Particularly for elite rugby kids, balance is key. So who’s falling foul of this today?

Hidden Figures

BACK IN 2019, Professor Henrietta Bowden-Jones opened the National Centre for Gaming Disorders – the first NHS-funded clinic. Then, she admits, there was a leap into the unknown. As she tells us: “When I started it, I didn’t know whether we’d manage to get 50 people, which is what we were commissioned to do for one year. But it’s been over a year and a half and we’ve gone to 250 people. So there clearly is a demand. And we treat patients and also their relatives.

“What I’m finding is the majority are young boys. Although I’ve had 20- or 30-year-olds coming through, there are very, very few. So what I’d love to know is in the sporting community, if there are people who have lost control of their gaming – either losing more money than they want to spend or are spending 14 hours a day gaming and it’s impacting on their relationships, jobs or lives. Right now I have no idea.

“This is the great thing about starting a national clinic. You have assumptions but you cannot go with them, you have to observe. It’s a free clinic. It has the best evidence-based treatment I can give, so there’s no reason people shouldn’t come forward.

“Now it’s possible that no one is coming forward because they don’t exist, right? So I go back to a prevalence survey. In gambling, I have some issues with how the methodology is conducted, but there is a somewhat research based (survey) being done by the Gambling Commission. In gaming there is nothing. So we have no idea of what the prevalence of gaming disorder is in this country.

Related: Rugby World’s Investigations

“We know globally it’s about 6%. I think that’s high for the UK but we don’t know the real percentage.” In 2021 we are in the dark about how worried we should be. But while global gamer numbers may wash over us, perhaps you saw the news out of China in August, when the country’s National Press and Publication Administration said that they’d curb gaming for under-18s to just an hour on Fridays, weekends and holidays. They even labelled gaming “spiritual opium”, adding: “No industry, no sport, can be allowed to develop in a way that will destroy a generation.”

Dramatic stuff, perhaps. Yet Professor Bowden-Jones reiterates the need for more to come forward if they are suffering and calls for a precautionary principle towards gaming while we await government reviews here. The positive thing, she says, is that we know behavioural addictions respond well to restructuring of behaviour, shaping of behaviour and treatment in general.

How many young footballers have been affected? (Getty Images)

If the clinic doesn’t see athletes by the maul-full, though, sports psychotherapist Steve Pope tells us he’s dealt with plenty of sportspeople in the last few years.

“It’s the silent epidemic really and it’s something we have to address,” he tells Rugby World. “The particular appeal to the sportsman is they can’t get tested for it. They can gamble, they can play games and do what they want for hours on end and there’s no test for it.

“Take football, for example. From the age of five or six the children have to be obsessional. They are obsessed and they possess some skill as well. When lockdown started there was very little else (for some young pro athletes) to do, besides gambling and playing games. So it got out of control, with many fitness regimes going out the window.

“The great test of the addict is if they started gaming and ten hours later they were still there. That was happening a lot. Though I have to say it quietened down when they got back to playing.”

Pope says gaming disorder, as it’s known now, is an issue he first worked on (amongst others) back in 2010. He says he was threatened then, that this was not seen as an addictive issue.

He does work with youngsters but there is an even mix of ages from 17 upwards, amongst sporting clients today, he says. What is clear, Pope adds, is that he is too often seen as a last resort. Maybe family life is impacted or a partner has had enough; training is being affected as sleep patterns fall apart; nutrition goes to hell; perhaps even substances are used during long sessions.

In terms of gamers, within pro sport, Pope says he works with around 15 regular clients. He also tells the story of one rugby international in the back-end of his career who was referred to him in 2010, with gaming negatively impacting his life more and more, causing him “marital disharmony”, as Pope calls it.

“This is non-selective. It can affect the guy who plays for Grasshoppers or the England international,” he says. “Confidence is a big thing in rugby, or soccer, and wanting a performance. You can use gaming to relax or enhance your ego, which is one I’ve dealt with before. It becomes a comfort blanket, takes away nerves and you get the desire to win but they can like the sensation, which appeals on another level too.”

The caveat that does come up on exploring this with the professionals is how we discuss excellence in this field – a growing and exciting frontier which we will come back to later. Nor are we saying those high-functioning, elite players who also excel online are doing anything wrong either. However, for all of us, it is okay to discuss addiction.

Understanding Addiction

THE WORLD Health Organisation (WHO) say gaming disorder is “a pattern of gaming behaviour (“digital-gaming” or “video-gaming”) characterised by impaired control over gaming, increasing priority given to gaming over other activities to the extent that gaming takes precedence over other interests and daily activities, and continuation or escalation of gaming despite the occurrence of negative consequences.

They state: “For gaming disorder to be diagnosed, the behaviour pattern must be of sufficient severity to result in significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning and would normally have been evident for at least 12 months.”

Scott Baldwin has talked openly on addiction (Getty Images)

If you thought a team-mate exhibited any of the above, would you raise it with them? Scott Baldwin would hope that you would. The ex-Wales hooker has been very open about gambling addiction, first revealing his troubles on Scrum V – an incredibly brave move.

He explains to Rugby World that he has an addictive personality and at his worst, he was “competing against the machine”, despite knowing that the odds were not in his favour. No matter what he was doing, he was thinking about gambling. He would lie in bed with his wife, he says, placing bets. In the end, the thing he had loved to win at most – rugby – was being negatively impacted by his desire to gamble.

So we come back to seeking help.

“It was consuming me,” Baldwin says. “I feel like that was probably more because I was keeping it secretive, I suppose. I was ashamed of it. Whereas I feel some boys now might be afraid to say, ‘I’ve got a gaming addiction.’

“They might be like, ‘What gaming? Come on, mate, really?’ But it’s an addiction. They can’t control that, they need help with it. So they need to be open and honest with people about it.”

Baldwin holds his hands up and says that he would never claim to know how prevalent detrimental gaming is across the sport, but he also says he has seen instances where young players cut the odd corner, after being up late gaming.

Baldwin says writing himself a note about gambling, putting it in black and white, helped him realise he did have an addiction. And if any young players ever want to talk to him about similar behavioral issues he is open to chats.

And while the Rugby Players’ Association (RPA) say they are yet to have a player raise gaming addiction as a primary concern, they do know a thing or two about behavioral issues.

According to Matt Leek, an RPA development manager in the South-West and a former educator, the key in the coming years is for the organisation to be proactive in identifying the looming threats to mental wellbeing amongst the athletes.

Could excessive gaming be a trigger or exacerbate long-standing issues? As Leek explains, usually the most vulnerable of elite athletes are those who are out with medium- to long-term injury and those transitioning into adult rugby, like the academy players. And while not mutually exclusive, it just so happens that such groups may include a number of gamers.

Leek also tells us that an increasing number of players who are referred to the RPA’s confidential counselling service do so on the back of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in their lives. So having supportive discourse around trauma and addiction is in the athletes’ interest.

Team Balance

YOU CAN be in danger of seeing this all from a place of the panicked, mind you. And the gamers deserve their say.

Jon Ellis has consulted with the Munster Rugby esports team (separate from the province) and is head coach at French side Solary’s League of Legends team. So he deals with the very best. And according to him, even in his field gaming disorder or addiction isn’t talked about as widely as it should be.

“What often happens is that people who are in this space tend to go really far one way and then people outside the space say gaming is really bad and evil go too far the other way,” Ellis begins.

“As with everything it’s really somewhere in the middle.”

A League of Legends competition in Iceland (Getty Images)

Ellis grew up with limited screen time as a child and he sees that some games are designed specifically to be rewarding. Yet the term ‘gaming addiction’ is so broad that we need to look at the differences between games – Minecraft users can create breathtaking designs within their worlds; League of Legends teams can work as a cohesive unit to achieve a goal. There are positives in so many, but when we do discuss addiction – which Ellis believes we should – be aware of the differences. Then let’s discuss shared responsibility.

Purely from a performance point of view, Ellis hates the idea of training hours stretching into the teens as players seek to improve. As with other elite sport, he trusts in recovery, nutrition, sleep, having a structured training week. More does not equal better, for him.

And just because your favourite streamer does something doesn’t mean it’s the only way to go. The other thing he has noticed is that the very best esports pros tend to also be the ones who did well in academics or practised rigour in their lives. “It’s stupid to try to be a professional gamer at the cost of everything else,” he adds.

Ellis Genge of Leicester Tigers and England (Getty Images)

Which brings us to balance. Ellis Genge has discussed openly the release valve gaming gives him and the friendships fostered, while others have excelled online. Jamal Ford-Robinson helped Jon Ellis coach during lockdown. If performance is not impacted, you can see why many athletes feel it enriches their life and fit it in around family time and training graft.

Related: Teimana Harrison on the gaming community

Some teams are happy to discuss how gaming slots into the squad ecosystem. As US Eagles sevens boss Mike Friday tells us when asked if he’s ever told a player to sort out their priorities: “There’s a happy medium to be had. If gaming is their way of escaping, if it allows them to destress and go to their happy place, then I’m all for it.

“When gaming is dictating them and keeping them up to all hours, those types of conversations that you’d have with your kids we’ve very much had! We have a lot of very good gamers as well and in the modern world earning income streams from esports and gaming is very much part of the landscape.

“Our perspective on it is that if we, like anything else, thought it was affecting their ability to prepare, train and perform, then of course we would address it with people. Yes, we’ve had general conversations about how to get a balanced life, to ensure that you’re doing all you need to do to enjoy life. But that’s just not restricted to gaming.”

Members of men’s US sevens side (Getty Images)

Rugby World understands that the Scotland men’s team have also talked with players about gaming, as part of their wellbeing talks, in relation to recovery, sleep and working towards a purpose. But like Friday, there is a belief that the sense of kinship, escapism and opportunity to build a brand is a plus.

Help At Hand

Holinski (EPIC)

AT EPIC, Mike Holinski, their head of sports partnerships, talks of loot boxes being a step towards gambling and detrimental behaviours around spending as one big example. He sees the positives for kids online, but hopes that education and discussion around the pitfalls can become more common – as much for parents and coaches as the young athletes. Not to create a bogeyman or incite panic, but to talk it through and give some the chance to discuss with their peers, or meet others.

The RPA are continually reviewing their education strategies and there is a need to be agile when assessing issues that may come up further down the line. For Professor Bowden-Jones, at the National Centre for Gaming Disorders in Earl’s Court, London, they are always open to referrals – and while elite athletes may see this, so might support staff or promising amateurs. You can email them at ncba.cnwl@nhs.net or call 020 7381 7722. RPA members can call Cognacity on 01373 858 080.

Download the digital edition of Rugby World straight to your tablet or subscribe to the print edition to get the magazine delivered to your door.

Follow Rugby World on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.