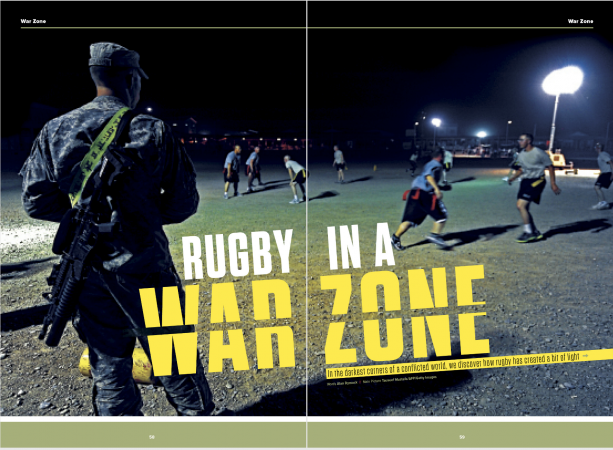

In the darkest corners of a conflicted world, we discover how rugby has created a bit of light. This feature first appeared in Rugby World in April.

Rugby In A War Zone

MARTYR DAY, in May 2014. Samer Al-Akhras will never forget it.

“I was a newly married man, so I was out with my new wife when the opposition started shelling the city,” the proud Syrian says. “Mortars landed near the restaurant we were in and a woman and her two teenager daughters were wounded. I went outside to provide first aid – I volunteered with Red Crescent for 12 years – and after providing the first aid, an ambulance arrived to take them.

“Another mortar fell and gifted me 1,200 (pieces of) shrapnel in my whole body. Five of them caused me bleeding inside the chest. Yeah, I was wounded.”

The woman, her daughters and all at the restaurant survived. But Al-Akhras’s abiding memory is not of falling horror in Damascus that day but of the bonds of rugby. Now administration manager for the Syrian men’s national 15s, Al-Akhras had only been playing for five months when team-mates from the Zenobians club rushed to his bedside. Overseeing his recovery, they allowed his wife to continue working and tend to family.

Flick on the news and the nightmares of conflict are unavoidable. But in all the darkness, rugby has offered some light. These are stories of how some around our mad world have turned to the sport…

Aftermath: A mortar attack in Damascus, 2014 (Getty Images)

SYRIA

AL-AKHRAS TALKS to us over Skype, however it takes time to make the connection. Damascus is experiencing one of their regular blackouts and he has to find one of the few internet cafés with power. Yet despite the ongoing civil war that began in 2011, he is upbeat.

No longer with his wife, they have a daughter named Souriana – “I named her after the country. I consider her the youngest rugby fan in Syria!”

His positivity pours from the pixels, even as he explains that power cuts are part of life here.

Shelling was no real surprise either. He explains that between 2012 and 2018, if it was a sunny day, you’d expect mortars from the likes of the Jaysh al-Islam militia.

Al-Akhras tells another story of a day when the Al-Fayha’a sports city, where the rugby team train, was shelled. No one from their side was hurt, but there were horrific casualties for the judo team in the complex then, with their head coach and three athletes killed.

In this environment, Al-Akhras calls it a “miracle” rugby has taken root. Now also an English instructor and humanitarian logistics adviser, he has seen the game flower in Damascus and Swida’a, and loves the efforts to take the game to more people in Syria. Team-mates may not know it, but he also credits them with helping him to recover from the psychological trauma of being wounded.

Positive: Syrian women’s players (Syria Rugby)

“I can’t explain the mix of feelings when you find all the rugby players in Syria behind you, whatever happened to you,” he tells Rugby World. “It’s not only helping me but it’s restoring the faith in humanity through rugby.

“There’s also a guy who plays with us. He was called for military service so that meant leaving his family behind, a mother, wife and two little kids. So the whole team is looking after them.

“This loyalty reflects onto him and today he’s fighting to find himself a place in the national team. He’s giving everything in the sessions to prove that he deserves it and he’s not missing any training. That is because of the unity and the family spirit we have within the rugby community in Syria.”

Related: Rugby project around the world celebrated in new issue

International sanctions mean it is difficult to find sponsors for their game. The improvements since 2014 are real. The Syrians are waiting for more help.

PALESTINE

THERE ARE unique challenges in bringing a diaspora of talent together under a flag, particularly in a region known for enmity. And according to Rabie El Masri, the president of the Palestinian Rugby Federation, it is far easier to organise get-togethers in the area known by some as Occupied Palestinian Territory, where there is better field access and greater numbers spread amongst two established teams. But bringing outsiders into Palestine or taking insiders out, is far, far trickier.

“‘Palestinian Refugees of Lebanon’ do not have the right to enter Palestine,” he says with a wry laugh. El Masri himself is a third-generation refugee, the second generation to be born in Lebanon, but because of his national status as being of Palestinian heritage, he says he can never represent Lebanon in any sports.

He goes on: “But Palestinians who live in Palestine don’t have the right to enter Lebanon too, unless we (arrange it) with an ambassador or

get special authorisation.

“So to gather for a (sevens event) in November in Jordan, we had the Palestinian refugees – which was difficult for visas and tickets – four players, and we had some from Palestine and more from Jordan. They were very motivated because it was all new for them.”

Groundbreaking: The Beit Jala Lions, 2008 (Getty Images)

An odyssey for recognition and a scramble to widen the player base began as an idea for El Masri while studying in France and has since led to him canvassing across Asia.

He can sense the need to push rugby, particularly in the refugee camps in Lebanon where, in the late 2000s Time wrote of “forgotten people” and Amnesty International saw “appalling social and economic conditions”.

El Masri tells us: “Rugby is a game with values that I need to give to youth in the camps. It helps build spirit and respect. It’s not always if you have a problem with someone that we have to use arms. In rugby you play physically and are still friends. These are courageous youths.

“Everybody saw them play – they were young but tackling like men. So rugby is perfect to gather people from different societies, different ways of living in the camp. Rugby can reduce the differences between them.”

His proudest moment? Seeing youths leave camps for rugby “scholarships”, earning discounted university places.

Rough road: A burned Ukrainian tank, 2015 (Getty Images)

UKRAINE

“The situation in the region has stabilised and military operations are almost over,” says Igor Yurkin of the Russian military intervention in Ukraine that began in 2014.

Yurkin is a big figure in both union and league around Donetsk. “The conflict is now just smouldering. It does not increase but it does not end either. The Donetsk region was divided into two parts – a part controlled by Ukraine and the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic. Donetsk resembles the grey zone, like the unrecognised republic of Transnistria.”

Related: Rugby photos to make you smile

In such areas, it is unsurprising that information on manoeuvres and political machinations would be tightly controlled. But take a walk down memory lane and the spirited Yurkin will happily tell you that before the occupation of Donetsk in 2014, the booming Tigers of Donbass youth club totalled 250 kids and 50 adult athletes and veterans. There were branches in Donetsk (three), in Avdeevka, Pesky, Makeevka, Yasinovataya and Krasnoarmeysk. They played the last Rugby Championship of the Donetsk region in Avdeevka in April 2014, after which hostilities began.

He also says that while circumstance and financial hardships have meant a rocky upbringing for the sport that first arrived there in 1985, “today rugby in Donetsk is experiencing a fifth revival.

Collective: Rugby teams in Donbass (Igor Yurkin)

“In 2014, when hostilities began, it hit rugby’s development hard. In Donetsk there remains one branch, which is trained on a voluntary basis. In territory controlled by Ukraine, rugby is left only in Pokrovsk. In 2015, a branch opened in Belozersk thanks to immigrants from Donetsk. In 2017, myself and Vladimir Lysenko created the Hard Sign club and in 2019 the Mariupol club started.

“There were also attempts to create branches in Aleksandrovka, Kramatorsk, Slavyansk, but they were unsuccessful. Here is such a difficult fate for rugby in the Donetsk region.”

Admirably, they keep rebuilding.

BURUNDI

THOUGH THE civil war erupted with a president’s assassination in 1993, the people of Burundi were no strangers to festering tensions, with a history of conflict between forces wishing to direct evil at ethnic groups: the Hutu or Tutsi.

As Céléstin Mvutsebanka, general secretary of the Burundi rugby federation, says: “The period has been characterised by a socio-political crisis which began with the assassination of Melchior Ndadaye in 1993 – the first elected president and first Hutu to reach this position in independent Burundi. But the crisis has its deep roots in the mismanagement of post-independence Burundi (a Belgian colony until 1962).”

Landlocked Burundi, neighbouring Rwanda, has known true horrors. Mvutsebanka says there was “an unprecedented tearing of the ethno-social fabric, exacerbating the tensions between Hutu and Tutsi” and that things did not de-escalate until the start of the 2000s, with the signing of the Peace and Reconciliation Agreement in Arusha, Tanzania, and then the Comprehensive Ceasefire Agreement of 2003.

“During this year of civil war, rugby like any other sport posted a negative record,” Mvutsebanka adds. “The Ceasefire Agreement allowed the entry of the CNDD-FDD into the transitional government and, with its leader Pierre Nkurunziza, to take the reins of the country, after the victory in the August 2005 elections. A new area is opening up for rugby and other sports in Burundi.”

Today Burundians are pushing the message of social cohesion and reconciliation. “Rugby has become the gateway to connecting different social trends,” says Mvutsebanka. “The creation of clubs almost everywhere in the country justifies a desire to mobilise a population who were at war for so long to be reconciled around the oval ball.”

White crowns: Kids in Rumonge (Burundian Rugby Federation)

He praises the involvement of political elites in Burundian sport. However, the nation saw fresh unrest in April 2015 when Nkurunziza declared his intention to run for a third term – an election he duly won. Critics called the move “unconstitutional”. Last year a UN commission called the government out for human rights abuses, while it’s been reported that more than a thousand people were killed during two years of unrest and that over 400,000 citizens fled the country.

It has since been stated that Nkurunziza will not run for re-election in May’s polls.

Politics aside, the union are sanguine. Rugby was introduced by European aid workers in the Seventies and the union was founded in 2001; there are now 12 top men’s clubs and seven for women. Mvutsebanka says up to 50 teams have competed to date in the inter-school championship.

Fostering ties across ethnic and class boundaries are a core tenet, the union say. Go to any youth event and you can see kids holding up white cards “as a symbol of peace”. In Rumonge the innovative children will also wear white paper crowns.

This feature first appeared in Rugby World magazine in April.

Can’t get to the shops? You can download the digital edition of Rugby World straight to your tablet or subscribe to the print edition to get the magazine delivered to your door.

Follow Rugby World on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.