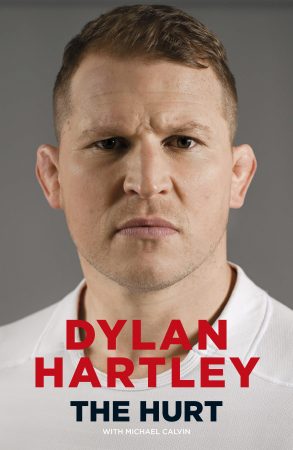

That's the sentiment of the former England captain's new autobiography, a book that Rugby World finds delightfully 'grubby'. Here's our review of The Hurt

Dylan Hartley, hurt but healed

If it feels like a long time has elapsed between Dylan Hartley playing rugby and putting out a book, there are two very good reasons for that.

The first is the practicalities around Covid, which delayed publication of his autobiography The Hurt by six months. The second is the doggedness of his character, the stubborn refusal to accept that his career was over because of the knee injury sustained against Newcastle in December 2018 and exacerbated a week later on Worcester’s artificial pitch.

Rugby World interviewed the former England captain two weeks before he finally announced his retirement on 7 November 2019 via Instagram, a post that generated 858 replies. “I need to keep trying. That resilience to chip away at the problem and to keep going is still there,” he told us, well aware by then that there would be no comeback.

The truth is out now – he apologises for fibbing through a studio interview with BT Sport – and comes in a beautifully written collaboration with Michael Calvin, a multiple winner at the Sports Book Awards. Calvin worked with Sir Alastair Cook, a Saints fan and friend of Hartley’s, so it’s easy to surmise how Hartley might have arrived at his choice of ghostwriter.

Red rose in bloom: lifting the Six Nations trophy in 2017, England’s second successive title (Inpho)

Those who say the book doesn’t sound like Hartley, that it lacks his ‘voice’, make a valid point. Yet it’s impossible not to be swayed by the quality of the prose, each chapter in its way a mini masterpiece. The ones titled Heart of Darkness and Own the Unexpected are this reviewer’s favourites and the latter contains a laugh-out-loud moment that encapsulates the stresses of working with England coach Eddie Jones.

Marland Yarde, the Sale wing, had driven down to the England team’s Surrey training base from Manchester after playing a Sunday afternoon match. Jones greeted him with: “How are you feeling, mate?”

‘Oh, a bit tired,” replied Yarde.

“F**k off, mate.”

“What?”

“If you’re tired, f**k off. I don’t want tired players here.”

You laugh because it’s so absurd and unreasonable, yet there is a serious message behind the harshness of life under Eddie. Even as tough a hombre as Hartley suffered mental burnout.

“The anxiety would begin to build even before I left home,” he says. “I would pack slowly, fighting my conscience at leaving my family, yet again. Farewells would become sadder because we knew I was going into a difficult situation. Underpinning everything was the understanding that… I would return home feeling like a dead man.”

Alliance: life with Eddie Jones was stressful but rewarding (Photosport/Inpho)

Perhaps we all overlooked how suffocating life was for Hartley as Jones’s captain, a job he did 29 times under the Australian (and with a remarkable 85% win rate). He was ‘on the clock’ from 6am to 9pm but that was when Eddie was in a good mood. “On bad days, when the phone pinged at 4am, our world was a wasteland.”

Press coverage of the book has focused on the abrupt way that Jones ended Hartley’s career, but the player’s respect for his long-time boss is evident. “Eddie had the knack of making you feel like you had learned something from his meetings. He got me thinking in a different way. He unlocked my mind.

“The critical difference between his approach and that of previous England regimes was the relentlessness of contact. He doesn’t stop. You wouldn’t want any other example from the man at the top.”

Certainly Jones comes out of the book in a more positive light than Hartley’s other England bosses, with failings expressed about the reigns of Martin Johnson (unwelcoming, sour atmosphere in camp) and Stuart Lancaster (kowtowing to the media).

Hartley told breakfast television viewers last week that the book looked at the “grubby” side of rugby. It’s an appropriate adjective. He talks about the dislocated shoulder from trying to clear out Jamie Gibson, the punctured lung tackling Richie McCaw. His wife, Jo, would bond his ears with surgical glue. He recalls a game at Penzance where he could hardly move when taking the field because his back was in spasm.

Concussion has a chapter to itself. In the 2016 Grand Slam match at Stade de France, Hartley was knocked our cold tackling 23st France prop Uini Atonio. It led to a worrying lack of “get up and go” and his second 45-day absence of that season.

Poleaxed: tackling Uini Atonio in the 2016 Grand Slam game…

…a clash that left Hartley badly concussed and condemned him to a spell on the sidelines (both Inpho)

Over his 15-year career, and including the unsuccessful 322-day battle to recover from his final knee injury, he lost more than three-and-a-half years to injury. He suffered six types of injury to his hands and wrists alone. “My generation of players have been crash test dummies for a sport in transition from semi-professionalism,” he says.

He advocates a six-month elite season, with successful clubs having their international players for 12-15 games a year. Contact training should be virtually non-existent, he argues.

On the personal side, Hartley’s family history is fascinating. One forbear helped Albert Einstein define the theory of relativity, and has an asteroid and moon crater named after him! He has Jewish heritage. Great grandfather Alfred won the Iron Cross in World War One and later fled Germany to avoid the Nazis.

A grand day out: with his wife Jo last year at Wimbledon, where he ran into Eddie Jones! (Getty)

Hartley grew up in Hamurana, near Lake Rotorua, the son of an English mother and New Zealander father. It’s pleasing to see so many photos in the book of him as a lad, fishing or quadbiking or playing with his two brothers on the family farm.

At his first rugby club, Ngongotaha, Hartley was one of just three white kids among Maoris. A loosehead prop in his youth, he played in the same Rotorua Boys High School team as Liam Messam and one that won numerous national titles.

At just 16, he came to stay with an uncle and aunt in East Sussex. Joining Crowborough RFC, by the end of the season he was in the England U18 squad. It was Worcester who gave his big break, putting him in their academy but on just £4,000 a year. He lived on pasta, tinned tomatoes and poached eggs but would pinch food when he could and sold England kit on eBay to make ends meet.

Hartley was wired a little differently from the rest. Playing in an U19 match against Leicester at Sixways, he saw an opportunity to take out the man barring his way to a place in the England age-group team. Finding himself over rival loosehead Kevin Davies, who was pinned to the floor, Hartley “unloaded a flurry of punches, UFC-style” on his adversary. Davies was substituted and never played for England again.

One parent branded him “a disgrace”; the RFU wanted him to see a psychologist. Hartley just focused on making the big time. He joined Northampton Saints, the club that turned him into a hooker, after asking if they wanted him. The main driver was their guarantee that he would be part of the first-team squad. “I wasn’t prepared to wait for tomorrow,” he says.

Try time: Hartley scores against Saracens, who he slates for flouting the salary cap rules (Getty Images)

To some extent, he sabotaged his own career because of the proliferation of suspensions. He was banned for a total of 60 weeks, the charge card including gouging, biting, abusive language and straight-arm tackles. He defends himself as he runs through the offences, not always convincingly. His reputation quickly preceded him and led to false accusations, such as a claim that he spat at a prone Welsh player in 2018.

The upshot was missed opportunities on the grandest stage. Only two men, Jason Leonard and Ben Youngs, have won more than Hartley’s 97 England caps. Yet only four of those 97 were won at a World Cup (2011) and there will not be one Lions tour to reflect on in his dotage. His big Lions opportunity, in 2013, disappeared after Wayne Barnes sent him off in the Premiership final. Regrets? I’ve had a few.

Not again: Hartley is sent off for elbowing Matt Smith during an East Midlands derby in 2014 (Getty)

Is he one of the greats? No one should underestimate his impact. As a scrummaging hooker he had few equals and he was as hard as they come, refusing to concede the fight even when the pressure exerted in the front row took him to the point of fainting.

From at first dreading the ball going off the field, he became a brilliant lineout thrower, recording a 93% accuracy rate internationally from the four-year cycle following the 2015 World Cup. He was not a showbiz player but a grafter, a ‘double rucker’ who would follow the ball with relish. “Tight rugby is my rugby,” he says. “I’m best suited to the old-school, up-the-jumper slog where conditions act as an equaliser.”

As a captain he promoted unity and cohesion in the group, getting players to put away their phones, take down their hoodies and move tables so they could develop friendships. He was loyal – turning down a big offer from Montpellier – and commanded enormous respect. Under his leadership, England went from eighth to second in the world in just four months and re-established themselves as a force to be reckoned with.

For all the bans and his roughneck image, Hartley can be proud of his rugby legacy. His autobiography is one of the first to be released this autumn and is sure to be one of the best.

Dylan Hartley: The Hurt is published by Viking, RRP £20.

Follow Rugby World on facebook, Twitter and Instagram.