Memoirs are rarely as entertaining as James Haskell's new book, finds Rugby World

James Haskell: what a flanker, what a book

Towards the end of James Haskell’s utterly compelling autobiography is a section titled No longer the dickhead. The ex-England flanker explains how he was portrayed as a dickhead by the media throughout his career, encountered countless people wary of him for that reason, and yet when he retired he was submerged by a tidal wave of affection from the public.

Haskell says: “One person wrote, ‘Why did it take for him to retire for people to be so nice to him?’ They had a point.”

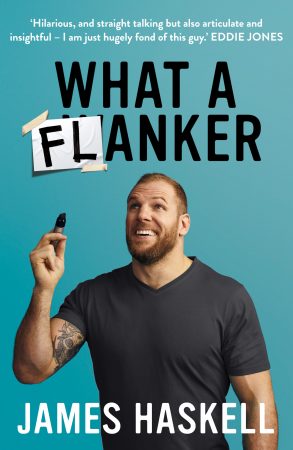

It’s why the book title, What a flanker, is so perfect. It reflects both the image he was lumbered with – via subtle word play, more apparent when you see the cover – and a rugby talent that earned him 77 England caps, the 14th most by an Englishman and third highest by a back-row behind Wasps team-mates Lawrence Dallaglio and Joe Worsley.

Haskell’s reputation didn’t spring from nowhere, there were incidents and events that fed it, rightly or wrongly. Mostly wrongly. I still recall clearly the hoo-ha surrounding him having a personal website when he was 18. Created by his father, it sparked the comments about ‘Brand Haskell’ and led to years of mickey-taking.

Was that fair? Of course not, but if you decide to do things differently from the norm you can put a target on your back. Haskell came up with a strategy. “I apply the rule that if 90% of people think something is wrong, then it’s wrong,” he says.

One of many: a Powergen Cup success with Wasps in 2005, a week after Haskell’s 20th birthday (Getty)

Of all the scrapes he got himself into, two in particular were to plague him and in his book he takes the opportunity to set the record straight. The first concerned the so-called porno movie with which he colluded with his best pal, Paul Doran-Jones, when the pair were schoolboys at Wellington College in 2003.

It was an idiotic thing to do but the storm that followed, including embellished news stories, front-page headlines, bullying of his kid brother and general humiliation for the Haskell family, was a heavy price to pay for his naivety.

Eight years later, he made an inappropriate remark to a maid in England’s hotel at the 2011 World Cup. Uttered in the company of Dylan Hartley and Chris Ashton and as Hartley was filming for a sponsor’s video, it triggered an avalanche of grief: false allegations, attempts at extortion, RFU bungling. The episode ended up costing Haskell more than £80,000 in legal fees and a contract with Melbourne Rebels.

Storm brewing: doing a bungee jump at RWC 2011, a stressful tournament for Haskell (Getty)

Haskell says he has learned that when adverse media stories arise, you should take matters into your own hands. Staying quiet and hoping it all blows away just doesn’t work.

Not that fronting up always leads to a happy outcome. Taking a stand against Wasps’ inadequate training facilities at Broadstreet led to a disgraceful lack of respect for the player at the end-of-season dinner that marked the end of his 12-year career with the club. He was placed at the back of the room by the bins and granted a derisory 30 seconds on stage. This for a former captain and a mainstay of their glory years in the Noughties.

Yet What a Flanker is not awash with negativity, far from it. In fact, it will make you laugh. A lot. Brilliantly crafted by ghostwriter Ben Dirs, it is packed with all manner of funny and/or jaw-dropping stories.

For example, there’s the one about Rory Best being pushed down a hill on a portable hospital bed, with near disastrous consequences. There’s the out-of-control Highlanders party at the house he rented off Seilala Mapusua. There’s the calendar shoot he did as part of joining Stade Français, when he had to prance like a pony stark naked on a car park roof overlooked by female office workers giggling at his petit appendage (it was a cold day, he says).

One anecdote concerns a session that John Wells did when he was England’s forwards coach. Wells wasn’t happy unless you were hurting each other, says Haskell, and during a training exercise where two people had to try to steal the ball off another, he would exhort the players to up their level of violence.

France were the upcoming opponents and Wells asked Tom Wood how he was going to get (Jean-Baptiste) Poux off the ball.

“Erm, twist his nuts off and snap his fingers?” Wood replied.

“That, Woody, is the best answer I’ve ever had!” said Wells, vibrating with excitement. “Now all of you, go out and show me that in training.”

On occasions, people’s identities are protected in the stories, although sometimes you’re able to hazard a guess as to who’s he talking about.

As we saw with Hartley’s book, Haskell viewed Eddie Jones as the best England head coach he played for. He won 15 caps under him when he thought that RWC 2015 would signal the end of his international career.

He says Stuart Lancaster treated players like kids whereas Jones treated them like adults and wanted to know their opinions. Haskell explains how Lancaster, in a David Brent-like moment, drew a ‘credibility graph’ to show that the flanker, who by this stage had 50-odd caps in his locker, was “nearly credible”.

In contrast, “Eddie backed me for who I was. Because of that mutual respect, he got the best out of me as a player. Eddie valued me because I wasn’t vanilla or run of the mill. He created an environment that was fun and I laughed every day I was with him in camp.”

Peas in a pod: Eddie Jones liked me because I had a personality, says Haskell in the book (Getty Images)

Haskell gives his views on individual players, on World Rugby’s shortcomings, on ‘fans’ who are crazy or weird or rude. He has trolled back the trolls and on one occasion even arranged a school visit to speak to kids who had abused him on Instagram. He slags off the media – who doesn’t, it seems – and explains how the makers of I’m a Celebrity stitched him up.

The pain that is intrinsic to playing elite-level rugby is covered in depth. It’s a subject that Hartley and Sam Warburton explored in detail in their memoirs and will inevitably recur as this generation retire with far more than bumps and bruises.

Haskell himself had ‘only’ four ops during his career, on an ankle, knee, toe and finger. Yet he wakes up in pain every day and can’t run anymore. He started seeing a psychologist when he was 17 and argues passionately about the value of nurturing mental health.

In his prime: carrying v Argentina in 2009, the year he was strangely ignored by the Lions selectors (AFP)

The ankle injury that flared up at Northampton at the end of 2018 effectively forced him to retire and it was a shock to him. “When I told my team-mates I was retiring I cried like a baby. For 25 years I’d spent almost every waking hour trying to be the best rugby player I could be. And now what was I? I felt like the prison librarian Brooks from The Shawshank Redemption, suddenly having to contemplate life in the real world.”

That new life includes a career in Mixed Martial Arts – on hold because of the pandemic – and two or three gigs a month as a DJ, in which he earns more money than he did playing for Saints. “DJ-ing has become my biggest passion in life. I’d honestly give up everything else if I could just do two or three DJ sets a week.”

The book manages to tick every box. It conveys the graft that went into making Haskell an international rugby player, it provides a platform for opinions formed from nearly two decades playing the sport. Yet it has lashings of humour and as certain anecdotes illustrate – the Joe Marler water-squirting incident, an exchange with Andy Farrell – Haskell is not afraid to be the object of mild ridicule.

“Everything I did – and I did a lot of stupid things – I did for the story,” he says. “All I ever wanted to do was to sit at the back of the coach, swap stupid tales and make people giggle.”

What a Flanker by James Haskell is published by HarperCollins, RRP £20.

Download the digital edition of Rugby World straight to your tablet or subscribe to the print edition to get the magazine delivered to your door.

Follow Rugby World on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.