Rugby's lax rules on nationality are creating more controversy than ever, with 134 foreign-born players selected to play at the World Cup in Japan. This is an advertising feature.

Naturalisation v nurture: Who wins from rugby’s eligibility laws?

The 2019 Rugby World Cup features a Scotsman playing for Canada, a Canada-born player with Ireland, an Irishman playing for the USA, an America-born star playing for England, an Englishman playing for Fiji, a Fijian playing for Australia, an Australian playing for Samoa, a Samoan playing for New Zealand and a New Zealander playing for just about everyone.

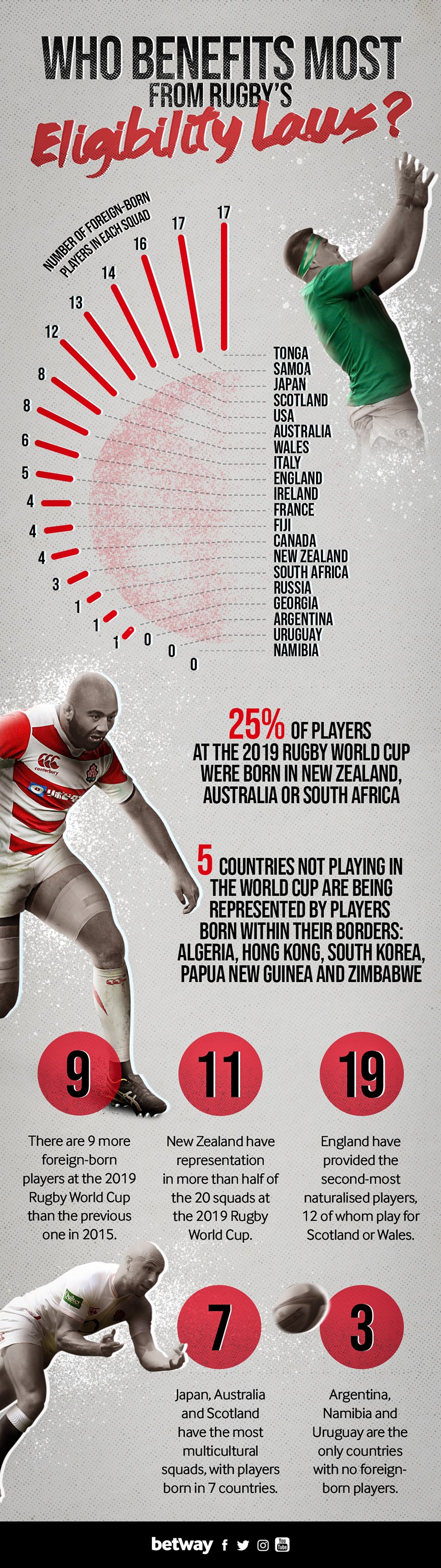

There are 134 foreign-born players at this tournament, according to figures compiled by Betway, who say that switching allegiances is, for better or worse, an intrinsic part of international rugby union.

Although there are several cases of players moving country when they are children, the ease with which adult players can move abroad, naturalise and begin representing a country to which they had no former ties is a loophole that has been exploited by most rugby-playing nations.

With the old laws, a player only needed to live in a country for three years before they become eligible for the national team.

By contrast, FIFA require footballers to live in a country for at least five years before they can take part in international football, with many associations enforcing additional restrictions on top of that.

Related: Read all about rugby’s eligibility law changes

Several high-profile omissions from the final squads for this year’s World Cup have brought the issue into even sharper focus this year.

England have selected scrum-half Willi Heinz, who was born and raised in New Zealand and has just three caps to his name.

Ireland have also been criticised for their decision to leave out 67-cap lock Devin Toner in favour of South Africa-born Jean Kleyn, who only qualified to play for them in August.

This graphic from Betway breaks down some key figures…

Things are, however, set to change, with World Rugby bringing their eligibility laws in line with FIFA by increasing the qualification period to five years at the end of 2020.

Driven by vice-president Agustin Pichot, this is an attempt to protect smaller nations from losing their best talents while helping all sides maintain their national identity.

How, then, are the new rules set to affect the landscape of international rugby union?

A look at the makeup of every World Cup squad and the statistics behind naturalisation at the tournament can help us find the answers.

There are nine more foreign-born players at this World Cup than the last.

Three countries – Tonga, Samoa and Japan – have more foreign-born players than home-grown. Scotland, the USA and Australia are not far behind.

However, Samoa and Tonga have never been beneficiaries of the system. They do, admittedly, field Australia-born and New Zealand-born athletes, but these are players with family ties to the Pacific. Players returning to their roots is not a phenomenon limited to rugby, and is not something that will change because of the new laws.

Samoa, Tonga and Fiji should, then, feel the positive effects of the imminent changes by being able to retain their best players over the coming years.

But the same cannot be said for the other four countries in question.

Unfortunately for Japan, the tournament hosts look likely to be hit hardest when the new rules come into play.

Their lucrative Top Rugby competition lures players from around the world, with most of their current foreign contingent qualifying after playing domestically for three years.

Five years is a different prospect entirely, and the Brave Blossoms will have to blood more local talent in the years to come.

This will likely mean an initial dip in performances on the pitch, followed by a slow improvement in the standard of Japanese rugby as youngsters are given more of a chance to flourish.

The USA will be in a similar position, with many of their foreign-born players qualifying during university stints or by playing in their burgeoning Major League Rugby competition.

Scotland and Australia, meanwhile, may lose out on a couple of potential ‘project players’ – those from abroad earmarked for naturalisation – but their relative riches should shield them from any real loss of depth after 2020.

That should be the case for the other top-tier nations, who will have enough domestic talent to make up for any loss of talent from abroad.

So, will the new rules have the desired effect? In a word, yes.

Bigger nations will be forced to use their own resources rather than poach from elsewhere, while smaller countries will become more competitive as they retain their best talent.

Players will be rewarded for their loyalty, not cast aside for a quick-fix foreigner, and the identity of every national team will slowly grow stronger.

Hopefully this is certainly a step in the right direction and one that will see international rugby evolve into a more competitive beast.

This piece is sponsored by Betway.

make sure you know about the Groups, Warm-ups, Dates, Fixtures, Venues, TV Coverage, Qualified Teams at the Rugby World Cup by clicking on the highlighted links.

Finally, don’t forget to follow Rugby World on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.