Find out what Test stars think about workload, concussion, money, agents and international rugby

Player welfare: two words that are now heard in rugby conversations almost as regularly as ‘try’ or ‘scrum’. Yet the people uttering the words are often in suits rather than kit, when surely it’s the opinions of the players themselves that are most important.

That’s why Rugby World magazine teamed up with International Rugby Players, the global body that represents the game’s professionals, to find out what their members think about the sport’s biggest issues. We’ve previously reported on the men’s sevens survey and women’s survey; now it’s time for the verdict of the men’s 15-a-side players.

More than 350 Test players from the 20 teams that will be involved at the 2019 Rugby World Cup, plus the other three nations involved in the repêchage and Romania, completed an anonymous survey on topics including workload, concussion, international rugby, agents and money.

Here are their views, as published in Rugby World’s January 2019 edition…

What the players think about rugby’s biggest issues: WORKLOAD

“Is what we’re doing to our bodies sustainable?” That is just one of the comments from those surveyed regarding the physical and mental load placed on players in the modern game.

It echoes the sentiments of Jonny May in the December issue of Rugby World, the Leicester and England wing saying: “I suspect that professional careers will grow shorter as players place increased loads on their bodies. The athletes will continue to get better, more powerful and more highly-tuned, but it will come at the price of not being able to do it for as long.”

People talk about how professional players are so much fitter and faster, bigger and stronger than the amateur era but, as May says, at what cost?

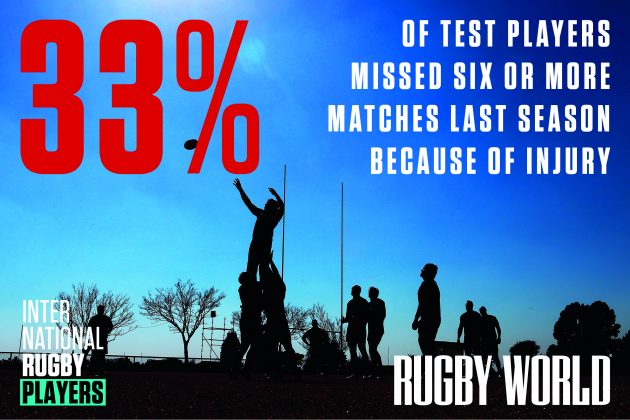

With improved physical specimens playing more high-intensity matches, players’ bodies are sure to feel the effects, whether in the long or short term. A third of the players surveyed by International Rugby Players missed six or more matches last season due to injury.

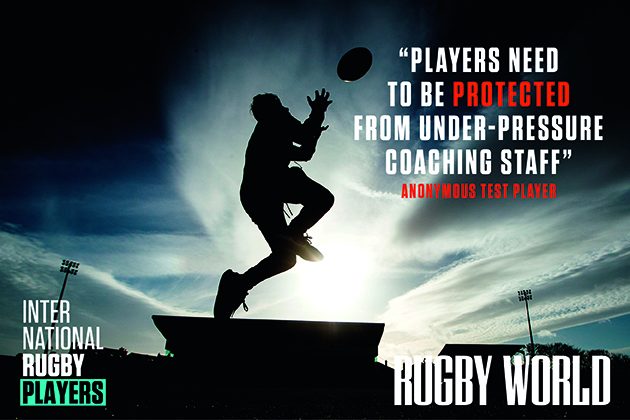

Even more shocking is that 45% of players – that’s basically one out of every two – admit to being pressured by coaches to play or train when not fully fit. Players often talk of carrying niggles throughout a season and with so much riding on matches it’s easy to understand why coaches want their star performers on the pitch, but players’ health should always be the top priority.

Clubs and governing bodies continually say player welfare is of the greatest importance, yet these results would suggest otherwise. Players should not have to train or play under duress, when doing so could cause more long-term damage. As one player surveyed said: “Players need to be protected from under-pressure coaching staff.”

International Rugby Players chief executive Omar Hassanein says: “Despite the constant reminder that player welfare is the game’s number one priority, it’s hugely worrying that a large amount of players have felt pressured to play when not fully fit. This leads to a spike in injury rates and we know from the survey that the biggest mental pressure comes from being injured.”

While 33% of players feel matches played is what has the most impact on physical workload in a season, it’s interesting that 30% cited the lack of recovery time, with this particularly high among Tier Two players.

People often praise the Irish system, where players are centrally contracted and rested at points in the season. The new season structure in England from 2019-20 will introduce in-season breaks for players, too, in an attempt to address the issue, but that plan still includes only two weeks of complete rest in the off-season.

Harlequins prop Joe Marler raised concerns about the new structure when it was first announced, but having spoken to his clubmate and RPA chairman Mark Lambert, he has revised his opinions – at least on some points.

“I think it’s good generally but there’s still work to do for England players,” he says. “The league is asking them to be available for more high-intensity Premiership games, to go toe-to-toe in full-on games as well as all the England games. So that needs to be looked at.”

That English structure also includes a maximum of 30 full games for players, yet the majority view of those surveyed is that 21-25 is the optimum number.

Former Wales and Lions captain Sam Warburton, who retired this year because he felt his body could no longer deliver the high standards he strived for, agrees on that point.

“The game is okay, it’s the amount of games that is the issue,” he told The Ruck podcast. “Rugby is never going to be safe – people might not want to hear that but you can’t get 30 big blokes running around a field and make it safe. You can’t make a ruck perfectly safe or a tackle perfectly safe. But what you can change is the workload on players.

“It’s more the volume that players are playing. On the Lions tour in 2017, some of the English guys were approaching 40 games – you can’t do that. I think 25 starts a season is ample.”

Another common talking point in recent years has been the amount of contact training undertaken by teams. With the increase in physicality, more strain is put on players in games and training. It was a common theme in survey responses.

Another common talking point in recent years has been the amount of contact training undertaken by teams. With the increase in physicality, more strain is put on players in games and training. It was a common theme in survey responses.

“Uncontrolled contact in sessions is problematic,” said one player. Another said: “Contact at training, whether in a club or international set-up, needs to be limited by time. There is enough contact week to week in games, so I don’t see why there is any in training.” A third player added: “Training is sometimes like match intensity.”

Interestingly, the NFL have established rules around training that limits the number of full-contact practice sessions in the regular season to 14, with 11 in the first 11 weeks, so a maximum of one a week. Team training is attended by independent observers to ensure these regulations are not breached.

So should rugby introduce something similar? Adam Beard, who has worked in rugby as a strength and conditioning specialist for Wales and the Lions and is now director of high performance at Cleveland Browns in the NFL, believes that cutting contact training back too much could actually mean that players’ bodies aren’t prepared for matches.

“It’s like UFC or boxing: you need contact, you need to prepare for contact,” says Beard. “These games are contact-orientated. We used to have a really big run-in for contact preparation for Wales. You would have a progression all the way through to bone-on-bone and some weeks we’d pull back, but we’d build it all the way through and guys’ bodies would be ready for that. It’s important for timing but also body conditioning. It’s a big thing, getting the body prepared.”

International Rugby Players are working with World Rugby to assess training load and whether players would benefit from restrictions.

It’s worth highlighting mental pressures as well as physical ones. Looking at the England structure from 2019-20 and those aforementioned breaks, Warburton insists it will still be hard to totally switch off in the middle of an intense season.

“There might be breaks but it’s a long time mentally,” he said. “Even if you’re physically helping a player, you’re not helping a player emotionally and mentally. It’s a long time in competition.”

The survey threw up similar concerns. One player said: “The season is too long mentally and physically.” Another said: “When you are on the fringe of your international side, doing the mental prep and playing limited minutes, then having to play in your break, it puts massive strains on relationships at home.”

Change: Quins prop Joe Marler has retired from international rugby (Getty Images)

You couldn’t describe Marler as a fringe international – he played 59 times for England between 2012 and 2018 – but the effect playing for his country had on his family life saw him call time on his Test career in September. How did that manifest itself?

“I’d be at home in a pretty dark place, not talking, not interacting with the kids or the wife,” says the 28-year-old. “My wife would say, ‘Any danger of you being here with us?’

“I’d be thinking about going away (with England) and having to leave Daisy and the kids. I’ve used the word anxiety because that’s how it felt. There’s a lot of pressure in any England environment and top-level elite rugby.”

He admits that when England opened their autumn campaign against South Africa, he woke up wishing he was playing at Twickenham. “But I quickly realised I didn’t miss it enough to do everything in order to get to game day – the three weeks beforehand, the time away from home. I make sacrifices for my club, for the team, but I also get to come home each night.”

Conversations around mental health are a lot more prevalent these days, not only in rugby but the world as a whole, with the sport’s player associations providing support programmes in this area. However, if changes in the game, such as the length of the season or number of Tests, would also help in

this area, they must be addressed.